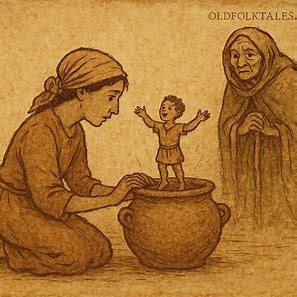

Once, long ago in the lands of the Bakongo people of the Democratic Republic of Congo, there lived a man named Tunga. He was not a poor man, for he had a house, a devoted wife, and a sweet little baby. Each day, Tunga ventured into the forest to set traps for birds and small animals. Partridges, guinea fowls, palm-rats, and squirrels often filled his snares, and at times he returned with three or four at once. One fortunate day, his traps yielded no fewer than fifteen plump partridges. Proudly, he carried them home and set them before his wife. She marvelled at the abundance and said gently, “Let us save some of these for tomorrow, so that our child will not go hungry if your traps are empty.” But Tunga, brimming with confidence, declared, “No, let us eat them all now. I am certain I will catch plenty every day.”

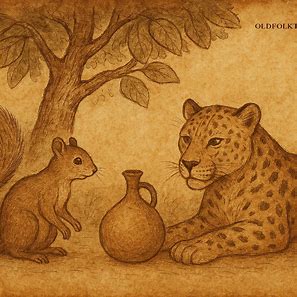

Not long after, Tunga went again to check his traps. To his surprise, only one creature was caught—a squirrel with tiny bells fastened around its neck. Tunga lifted his hand to strike, but the squirrel spoke in a trembling voice, “Please, do not kill me. If you spare me today, I will help you in your time of need.”

Tunga laughed. “How can a small creature like you help a man?” Yet the squirrel pleaded so earnestly that Tunga’s heart softened. He released it and returned home with only leaves in his basket.

When he told his wife what had happened, she grew angry. “You brought no food for our baby? You let a meal slip away for a promise?” Quarrels flared, and in her frustration, she took the child in her arms and left to stay with her family in a distant town.

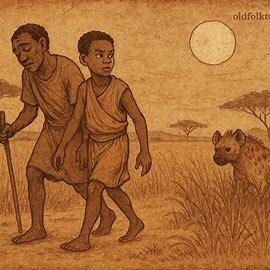

For several days Tunga remained alone. At last, when his wife’s absence weighed heavily on him, he resolved to follow her. He filled a large calabash with palm-wine and set off. Along the road he reached a crossroads where he met a strange being, an Imp with no arms, legs, or body, only a great bouncing head. The Imp called out, “Let me carry your calabash. A man as great as you should not burden himself.”

Puzzled, Tunga asked, “How can you carry it, when you are nothing but a head?”

“You shall see,” replied the Imp. Balancing the calabash neatly, he bounded down the path with ease, while Tunga followed behind.

After some distance, the man grew tired, and they sat under a tree to rest. As they sat, a leopard approached, its eyes glinting with hunger. The beast fixed its gaze on the calabash and demanded, “Give me a drink!” Terrified, Tunga dared not refuse. He reached to pour wine into a cup, but the leopard snarled, “I drink from my own mug.” From its bag, the leopard drew out the skull of a man. “This is my cup. I have eaten nine men already, and you shall be the tenth.”

Tunga trembled, unable to speak. At that very moment, the squirrel appeared. After exchanging greetings, it too asked for wine. Tunga, relieved, reached again for his cup, but the squirrel said sternly, “What? Do you not respect me? I drink from my own mug.” Reaching into its bag, the squirrel produced the skull of a leopard. “Here is my cup. I have eaten nine leopards, and you will be the tenth.”

The squirrel repeated this fierce threat again and again until the leopard shook with fear. Slowly, it backed away, then turned and fled into the forest. The squirrel chased after it, leaving Tunga in awe of the promise fulfilled. Grateful, he continued on with the Imp toward his wife’s town.

When they arrived, Tunga was warmly welcomed. He was given a fine house, food, and rest. After several days, he and his wife reconciled, and together they prepared to return home. As a parting gift, her family presented them with a goat.

READ: The Kingfisher and the Owl | A Bakongo Folktale from the Democratic Republic of Congo

At the crossroads once more, Tunga said to the Imp, “Here we shall kill the goat and share it. You may have half.”

The Imp replied, “That is fair, but you must also give me half the woman.”

“No,” Tunga protested, “she is my wife. You may have half the goat, but not her.”

Enraged, the Imp called upon his fellows, and soon a crowd of them gathered, pressing to fight. Just as the quarrel threatened to spill into violence, the squirrel arrived again. “What is this commotion?” it asked. Tunga explained, and the squirrel said, “If you divide the goat and the woman, how will you cook them? You have no firewood and no water.”

The squirrel handed the Imps a calabash, instructing some to fetch water and others to collect firewood. Yet as water poured into the calabash, it began to sing a magical tune. The Imps, unable to resist, danced wildly, trapped in endless movement. The squirrel then opened a box, releasing a swarm of bees that stung the remaining Imps until they scattered, never to return.

Turning to Tunga, the squirrel said, “Now you see. Your kindness in sparing me saved not only your life but also your wife’s. Mercy brings its own reward.” Tunga, humbled and grateful, thanked the squirrel and journeyed home in peace.

Moral Lesson

This Bakongo folktale teaches the value of mercy, patience, and foresight. Tunga’s kindness to the squirrel, though mocked at first, became the very key to his survival. The story reminds us that compassion toward even the smallest beings may yield blessings in unexpected ways. Rash decisions and arrogance, like Tunga’s initial wastefulness, bring hardship, but humility and mercy build lasting protection.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who was Tunga, and what did he do for a living?

A1: Tunga was a hunter who caught small animals in traps.

Q2: What creature did Tunga spare that later helped him?

A2: A squirrel with bells around its neck.

Q3: How did the leopard threaten Tunga?

A3: By demanding palm-wine in a human skull, boasting it had eaten nine men.

Q4: How did the squirrel scare away the leopard?

A4: It claimed to have eaten nine leopards and threatened to make this one the tenth.

Q5: Why did the Imps attack Tunga?

A5: Because he refused to give them half of his wife as part of their bargain.

Q6: What cultural values of the Bakongo people are highlighted in this tale?

A6: Mercy, resourcefulness, and the importance of keeping promises.

Source: Bakongo folktale, Democratic Republic of Congo.