Winter had descended upon the Great Karroo with a vengeance. The evening air was so sharp and biting that you could almost hear the frost forming on the sparse vegetation scattered across the endless plains. A thin wind what the locals called a skraal windje whispered down from the distant mountains, carrying with it the mingled scents of karroo-bush, sheep pens, and wood smoke from the nearby huts. These aromas, each unremarkable on its own, blended together in that rare, crystalline atmosphere to create something almost intoxicating in its freshness.

Young Pietie van der Merwe stood at the farmhouse door, peering out through the upper half into the pale moonlight that bathed the landscape in silver. He took several deep, appreciative breaths before the cold finally drove him back inside. With an involuntary shiver, he closed the door and turned toward the welcoming warmth of the crackling fire, where his brother Willem sat contentedly feeding mealie-cobs into the flames from a basket at his side.

In the corner of the wide, old-fashioned rustbanka , traditional South African bench, little Jan sat perfectly still, his large grey eyes gazing wistfully into the red heart of the fire as if searching for pictures in the dancing flames. His hand moved absently through the fur of Torry, the family’s fox terrier, who lay curled beside him in contented slumber.

Explore more Southern African folktales here

Their mother occupied her customary place in the big Madeira chair at the side table, occasionally yawning over her book. Whether winter or summer, the mistress of a Karroo farm lived a demanding life, and by evening’s end, she had more than earned her rest.

The door at the far end of the room opened, and Father entered with the unhurried comfort of a man at peace with his world. Nothing in his relaxed demeanor suggested the demanding physical labor of shearing, dipping, and ploughing that filled his days. Yet his healthy tan, broad shoulders, and robust physique told the true story of his strenuous outdoor life. His eyes swept the scene before him with quiet satisfaction,the bright fire casting dancing shadows on the painted walls and polished woodwork, the table set for the evening meal, his children gathered at the fireside, and his beloved wife who made their home a haven of warmth and happiness.

Close behind him came Cousin Minnie, the bright-faced young governess whose arrival caused an immediate stir among the children. Little Jan slowly withdrew his gaze from the hypnotic flames and, with surprising energy for one who had appeared so dreamy, pushed and prodded the sleeping terrier along the bench to make room for her.

Pietie sprang to his father’s side with barely contained excitement. “Now may I go and call Outa Karel?” he asked eagerly. At his father’s acquiescent nod, the boy flew from the room as if his feet had sprouted wings.

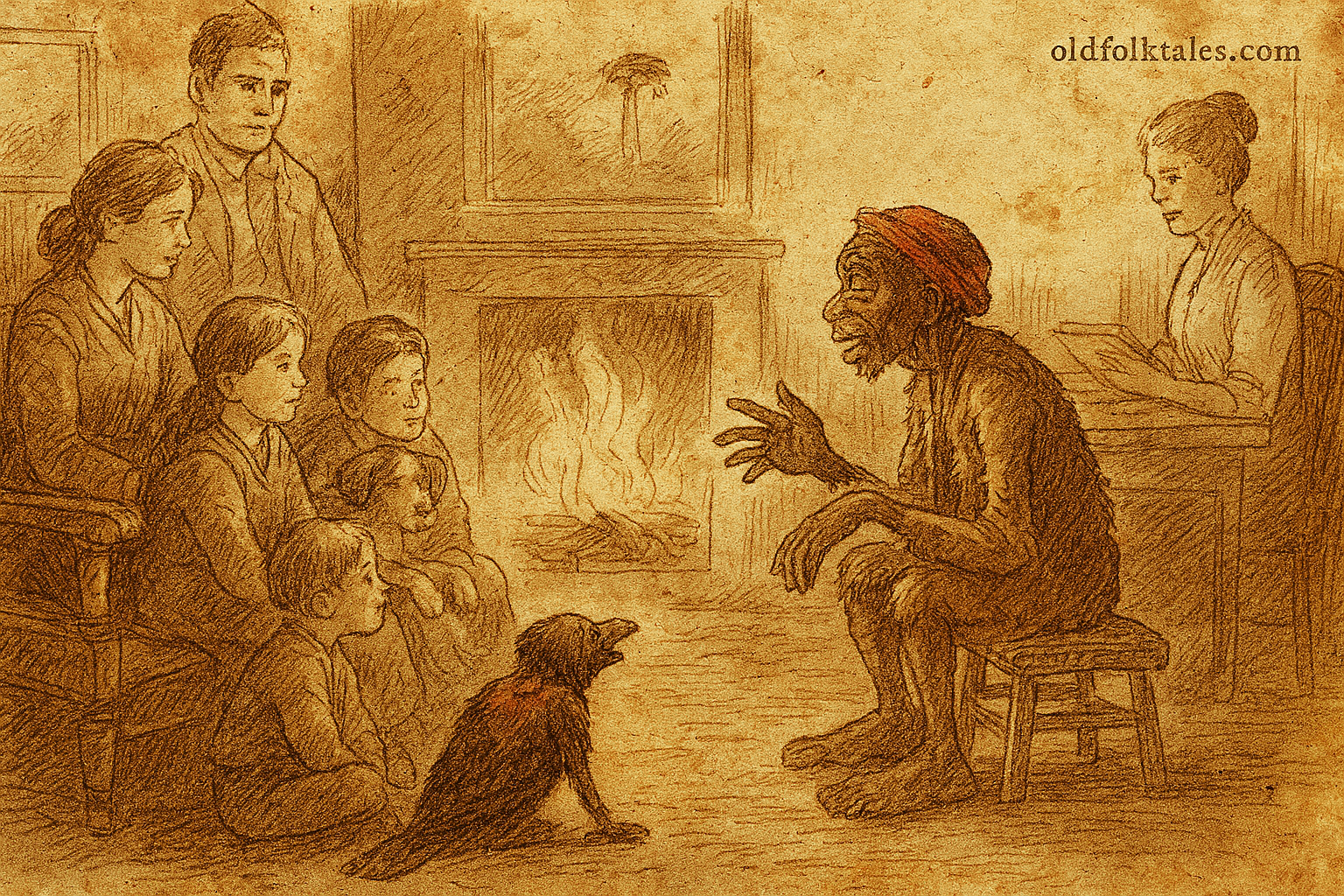

The figure that appeared moments later was truly extraordinary. Shuffling, stooping, and halting with each difficult step, he finally emerged into the firelight, a vision that might have sent a stranger fleeing in terror. For Outa Karel looked remarkably like an ancient, muscular gorilla dressed in human clothing and walking uncertainly on his hind legs.

Standing not quite four feet tall, he possessed shoulders and hips disproportionately broad for his frame, with long arms whose hands reached nearly to his knees. His lower body was clothed in strange garments fashioned from wildcat and dassie skins, while a faded brown coat obviously once belonging to his master, hung almost to his knees. When he removed his shapeless felt hat, a red kopdoek (head cloth) could be seen wound tightly around his skull. Rumor had it that beneath this cloth, his head was as smooth and hairless as an ostrich egg.

His yellow-brown face resembled a network of deeply etched wrinkles, across which his flat nose sprawled broadly between prominent cheekbones. His eyes, sunk deep into their sockets, glittered dark and beady like a snake’s eyes peering from a shadowy hole among rocks. Yet his wide mouth twisted into an engaging, ear-to-ear grin as he blinked and winked, twirling his old hat in claw-like hands while attempting to bow to his master and mistress.

The stiffness of his joints made the gesture unsuccessful, but it never failed to amuse the family, who had witnessed it countless times. Despite his grotesque, disproportionate form and ape-like features, there was something unmistakably human and endearing about him. Humor and kindness gleamed from those cavernous eyes, which at first glance seemed designed only for malevolence and cunning.

Outa Karel represented one of the last remnants of an ancient race, the Bushmen, South Africa’s original inhabitants who had been pushed from their ancestral lands by successive waves of conquest. First came the Hottentots, then the powerful Bantu peoples, and finally the pale-faced Europeans from across the seas. Though Outa always claimed pure Bushman heritage, the strong Hottentot strain in his build told a more complex story of his ancestry.

“Ach toch! Good night, Baas. Good night, Nooi. Good night, Nonnie and my little baasjes,” he said in Dutch, his voice honey-sweet with deference. “Excuse that this old Bushman does not bend properly to greet you; the will is there, but his knees are too stiff.”

Pietie dragged a low stool covered with springbok skin from under the desk and pushed it toward him. With much creaking of joints and many strange native exclamations, Outa settled himself carefully.

The family rearranged themselves in anticipation. Cousin Minnie nestled in the corner of the rustbank, with little Jan’s head resting against her and Torry’s head on Jan’s lap. Father positioned himself at the other end with his magazine, while Willem sat on the floor against Cousin Minnie’s knee, and Pietie claimed a small chair directly before the fire.

All eyes turned to the ancient storyteller, who now lived as a privileged pensioner among the van der Merwe family he had served faithfully for three generations. The firelight played over his strange figure with eerie effect, illuminating now one feature, now another, throwing exaggerated shadows on the wall as his small hands gestured incessantly, for his people spoke as much through movement as through words.

This was the children’s beloved hour, when the short winter day had ended and, in the precious interval between darkness and dinner, their dear Outa Karel was permitted to entrance them with his tales, weird and wonderful stories of spirits and giants, talking animals, and creatures that wielded mysterious influence over unsuspecting humans. Most thrilling were his personal adventures with lions, leopards, jackals, and crocodiles.

“Now, Outa, tell us a nice story, the nicest you know,” commanded little Jan, nestling closer to Cousin Minnie.

“Ach! But klein baas, this stupid old one knows no new stories,” Outa began with practiced cunning. “And how can he tell even the old ones when his throat is so dry, ach, so dry with dust from the kraals?”

He forced a theatrical cough, his beady eyes glittering expectantly. Then he started with exaggerated surprise as Pietie appeared beside him with a glass of brandy,the soopje kept especially for him.

This nightly performance never varied. The drink was never forgotten, but often purposely delayed to see what creative excuse Outa would devise. Tonight, having received his reward, he lifted the glass ceremoniously.

“Thank you, my klein koning! Gezondheid to Baas, Nooi, Nonnie, and the beautiful family van der Merwe!” He gulped the contents and smacked his lips. “Ach! If only a Bushman had a neck like an ostrich! How good the soopje would taste all the way down! Now I am strong again; now I am ready to tell my story of Jakhals and Oom Leeuw.”

And with that promise hanging in the air, the ancient storyteller prepared to weave his magic once more.

Moral Lesson

This story celebrates the importance of preserving oral traditions and honoring those who carry the wisdom of previous generations. Despite Outa Karel’s humble status and unusual appearance, he holds a treasured place in the family because of the cultural heritage and stories he preserves. The tale reminds us to respect our elders, value diverse cultures, and recognize that a person’s worth lies not in their appearance or social position, but in the knowledge, kindness, and humanity they embody.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who is Outa Karel and what is his role in the van der Merwe family? A: Outa Karel is an elderly Bushman storyteller who served the van der Merwe family faithfully for three generations. Now a privileged pensioner on their Karroo farm, he entertains the children each evening with traditional tales and legends, serving as a living link to South Africa’s indigenous heritage.

Q2: What is the significance of the Great Karroo setting in this story? A: The Great Karroo is a semi-desert region in South Africa that serves as the story’s atmospheric backdrop. The harsh winter landscape and isolated farm setting create the perfect environment for intimate family gatherings around the fire, where oral storytelling traditions thrive and cultural heritage is preserved through Outa Karel’s tales.

Q3: What cultural heritage does Outa Karel represent? A: Outa Karel represents the Bushmen (San people), one of South Africa’s original indigenous populations. Though he has some Hottentot ancestry, he embodies the vanishing traditions of an ancient people who were displaced by successive waves of conquest—first by Hottentots, then Bantu peoples, and finally European settlers.

Q4: Why do the van der Merwe children eagerly anticipate Outa Karel’s storytelling sessions? A: The children treasure these evening storytelling sessions because Outa Karel brings history alive through dramatic tales of spirits, talking animals, and thrilling personal adventures. His theatrical delivery, complete with gestures and voice changes, creates an immersive experience that captivates their imaginations and connects them to their cultural landscape.

Q5: What is the significance of the “soopje” ritual before Outa Karel tells his stories? A: The “soopje” (small drink of brandy) is a time-honored custom that shows respect and hospitality. Outa Karel playfully delays beginning his stories until offered this drink, turning it into a theatrical performance that the family enjoys. The ritual demonstrates the affectionate, teasing relationship between the storyteller and the family he serves.

Q6: What does this story teach about valuing people beyond their appearance? A: Despite Outa Karel’s unusual, almost frightening appearance and low social status, the van der Merwe family treasures him for his humanity, loyalty, and the cultural wisdom he carries. The story teaches that a person’s true worth lies in their character, knowledge, and the kindness they show others, not in their physical appearance or social position.

Cultural Origin: South African folktale tradition, Great Karroo region. Story collected by Sanni Metelerkamp, featuring Bushman (San) cultural heritage.