Long ago, in the northwestern reaches of Singapore, there stood a banyan tree so ancient and enormous that its gnarled roots seemed to grip the very soul of the earth. Its massive canopy spread like a dark umbrella at the entrance to a small village, casting shadows that grew longer and more menacing as the sun descended each evening.

The villagers had grown to despise this tree. Not only did its sprawling trunk and twisted roots block the main path into their settlement, forcing them to take lengthy detours with their carts and livestock, but something far more sinister dwelled within its branches. Every night, without fail, a haunting melody would drift down from the dense foliage, a tune so enchanting yet so unnatural that it seemed to seep into the very bones of anyone who heard it. Within moments of the music beginning, every man, woman, and child in the village would collapse into a deep, unshakeable slumber.

Click to read all Southeast Asian Folktales — featuring legends from Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

Morning always brought the same grim discovery. As the villagers stirred from their enchanted sleep, rubbing their eyes and shaking off the strange heaviness that clung to their limbs, they would find fresh evidence of the night’s dark deeds. At the foot of the banyan tree lay scattered bones, the remains of chickens that had vanished from their coops and goats that had disappeared from their pens. The animals had been completely devoured, leaving only white bones picked clean and gleaming in the dawn light.

The mystery tormented the villagers. Hussein, one of the village elders, stood beneath the tree one morning, scratching his graying head in utter dismay. “We don’t know what manner of creature lives inside that tree,” he said, his voice heavy with worry.

“We have to destroy it! The tree is cursed!” Ishyak exclaimed, his hands trembling. His small house sat closest to the banyan tree, and he was always the first to succumb to the mysterious music, often collapsing in his doorway before he could even secure his door for the night.

Daud, a farmer with calloused hands and a weather-beaten face, looked down at his five hungry children clustered around him. “I have lost all of my chickens,” he lamented, his voice breaking. “I can’t afford to lose any more goats! How will I feed my family?”

The village chief, a man of decisive action, finally declared that the time had come to confront whatever evil resided in that tree. As the sun began its descent that evening, he gripped his spear firmly and commanded the men to gather their weapons and torches. They formed a circle around the massive banyan tree, their flaming torches casting dancing shadows across its bark.

“Now!” shouted the chief, and as one, the men hurled their torches at the tree. But the moment the flames touched the branches, that same chilling, otherworldly music resonated from within the foliage. The melody wrapped around the men like invisible chains, and one by one, they crumpled to the ground, overtaken by the spell.

All except Ali. Born without hearing, Ali stood alone among the sleeping men, immune to the magical music. His eyes widened in horror as the charred branches crackled and parted, and from within emerged a creature from nightmares—a gigantic snake with red, patchy skin that seemed to glow in the firelight. Its body was as thick as a tree trunk, and it slithered out slowly, deliberately, its tongue flicking as it surveyed the sleeping men.

“Wake up! Wake up!” Ali cried desperately, his voice growing hoarse, but the snake’s spell was too powerful. The serpent hissed at him, a sound Ali could not hear but could feel vibrating through the ground. Then inspiration struck. Ali ran to the nearby well, his feet pounding against the earth. He hauled up a bucket of cold water and rushed back, splashing it across the faces of his fallen comrades.

“Wh…what happened?” Hussein muttered, sputtering and disoriented. But before anyone could answer or gather their bearings, the enormous snake lunged at them with frightening speed. The men scattered, then rallied, striking at the reptile’s body with their spears, swords, and clubs. But their weapons bounced off harmlessly, the creature’s body was as hard as rock, impervious to their attacks.

Terrified and exhausted, their arms aching from futile strikes, the men finally abandoned their weapons and fled to their homes, shame and fear mingling in their hearts.

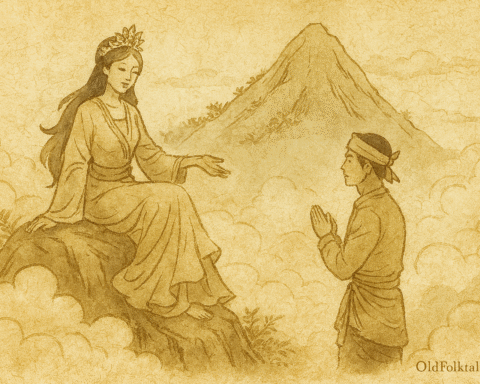

That night, as the villagers lay in their beds tossing and turning, a vision came to them, all of them, simultaneously, as if sent by divine intervention. In their dreams, they saw the solution clearly: the snake could only be destroyed by special fire stones that would burn when water was added to them. But they would have to wait until the next lunar month, when the wicked serpent would drift into its deep seasonal sleep.

The days crawled by like wounded animals. Then weeks passed, each one feeling like an eternity. The villagers prepared in secret, gathering the rare fire stones from the hills and planning their attack. When the appointed time finally arrived, they assembled once more at the banyan tree, their hearts pounding with determination and hope.

The men began hurling the fire stones at the tree with all their strength, then flinging buckets of water at them. The stones ignited upon contact with the water, creating flames hotter than any normal fire. The tree shook violently, its branches writhing as if in agony, and a portion of the massive snake’s body rolled out from the blazing trunk.

Immediately, arrows flew through the air, striking the serpent in its head. Still, even wounded and burning, the snake attempted to play its hypnotic music. “Stuff your ears with cloth!” Ishyak shouted, and the men quickly tore strips from their clothing to block their ears.

Unable to entrance its attackers, the snake was powerless. The villagers pressed their advantage, striking again and again with renewed courage. After countless blows from spears, axes, and stones, the great serpent finally squirmed, quivered, and collapsed to the ground like a massive, felled log.

The villagers, remembering all the livestock and peace the creature had stolen from them, decided to punish the snake even in death. They carefully skinned the enormous reptile, stretching its distinctive, red-patched skin tightly over a large wooden bowl. Someone struck the skin experimentally, and to everyone’s surprise, it produced a deep, resonant sound. As more people took turns beating the skin, each strike created different tones. When played together in rhythm, the sounds formed music that was rather delightful, far more beautiful than the snake’s cursed melody had ever been.

And thus, the kompang was born, a traditional frame drum that would become central to Malay celebrations and ceremonies for generations to come.

Journey through enchanted forests and islands in our Southeast Asian Folktales collection.

The Moral of the Story

This tale teaches us that even from the darkest evil and greatest fear can come something beautiful and meaningful. The villagers’ courage and unity transformed their tormentor into an instrument of joy and celebration. It reminds us that communities grow stronger when they face challenges together, and that perseverance and creativity can turn curses into blessings. The kompang stands as a symbol that we should not let fear paralyze us but instead find ways to overcome adversity and create beauty from hardship.

Knowledge Check

Q1: What was the Giant Snake of the Banyan Tree and what powers did it have?

A: The giant snake was a cursed serpent with red, patchy skin that lived inside an enormous banyan tree in a Singaporean village. It possessed magical powers to create hypnotic music that put all listeners into a deep sleep, allowing it to steal and eat the villagers’ chickens and goats. Its body was also as hard as rock, making it nearly invulnerable to ordinary weapons.

Q2: Why was Ali the deaf villager important to the story?

A: Ali was crucial because his deafness made him immune to the snake’s magical, sleep-inducing music. When all the other villagers fell under the serpent’s spell during the first attack, Ali alone remained awake and witnessed the creature emerging from the tree. He saved his fellow villagers by splashing them with cold water to wake them, and his unique perspective helped the community realize they needed to protect themselves from the music.

Q3: What were the fire stones and how did they help defeat the snake?

A: The fire stones were special magical stones revealed to the villagers through a collective dream vision. Unlike ordinary stones, these would ignite and burn intensely when water was added to them. The villagers used these stones to set the banyan tree ablaze during the snake’s deep seasonal sleep, which finally wounded the serpent enough that they could defeat it with conventional weapons after blocking their ears against its music.

Q4: What is a kompang and how did it originate according to this Singapore folktale?

A: A kompang is a traditional Malay frame drum used in celebrations and ceremonies. According to this folktale, the kompang was created when the villagers skinned the defeated giant snake and stretched its distinctive red-patched skin over a wooden bowl. When they beat the skin, it produced beautiful, resonant sounds, transforming the source of their fear and suffering into an instrument of joy and music.

Q5: What does the banyan tree symbolize in this Singaporean legend?

A: The banyan tree symbolizes both obstacle and evil in the story. Its enormous size blocked the village entrance, representing physical barriers in life. More significantly, it housed the cursed snake, making it a symbol of hidden danger and the unknown fears that communities must face together. The tree’s destruction represents overcoming these obstacles through courage and unity.

Q6: What cultural lesson does the origin of the kompang teach in Malay tradition?

A: The origin story of the kompang teaches that communities can transform evil and suffering into beauty and celebration through courage, cooperation, and creativity. It emphasizes the importance of facing fears together rather than fleeing from them, and shows how perseverance can turn a curse into a blessing. The kompang itself becomes a reminder that even our greatest challenges can become sources of joy and cultural pride.

Source: Singaporean folktale