On the wide Ogun River, where the water holds the color of palm bark and the morning mist sits like an old woman’s shawl, lived Ayo, a fisherman whose nets often returned as light as a whisper. He rose before the first rooster’s breath, he hummed his mother’s prayers, and he cast his nets with care. Yet fortune seemed to pass his canoe the way a young goat slips past a sleepy gatekeeper. Still, Ayo shared his meager cassava and smoked tilapia with neighbors, and he spoke to strangers with the warmth of garri in hot water.

One harmattan morning, when the air tasted of dust and memory, Ayo found a gourd bottle tangled in his net. The gourd was sealed with cowrie shells and smeared with red camwood, the sign of something sacred. He turned it in his hands, listening for the hush of the river inside. An elder on the bank called out, careful, son, not all gifts like to be opened. Ayo nodded, thanked the elder, and set the gourd near his paddle, letting his net glide again into the brown-green river.

The sun climbed slowly, bright as a drum skin. Still no fish. Ayo looked at the gourd and remembered his mother’s words, kindness is a paddle that turns the canoe of fate. He poled toward the western reeds, where a child was crying. A small boy stood barefoot on the muddy bank, staring at a broken basket that had once held yams. In the shallows lay the scattered yams like fallen moons. My mother will weep, the boy said, we have nothing else to sell. Ayo nodded, moved his canoe close, and gathered the yams one by one, rinsing them gently. He repaired the basket with a thin reed from his spare rope, his fingers moving with the patience of river stones. Take this fish when your mother comes, he said, dropping his last smoked tilapia into the basket. The boy bowed, his eyes bright with surprise.

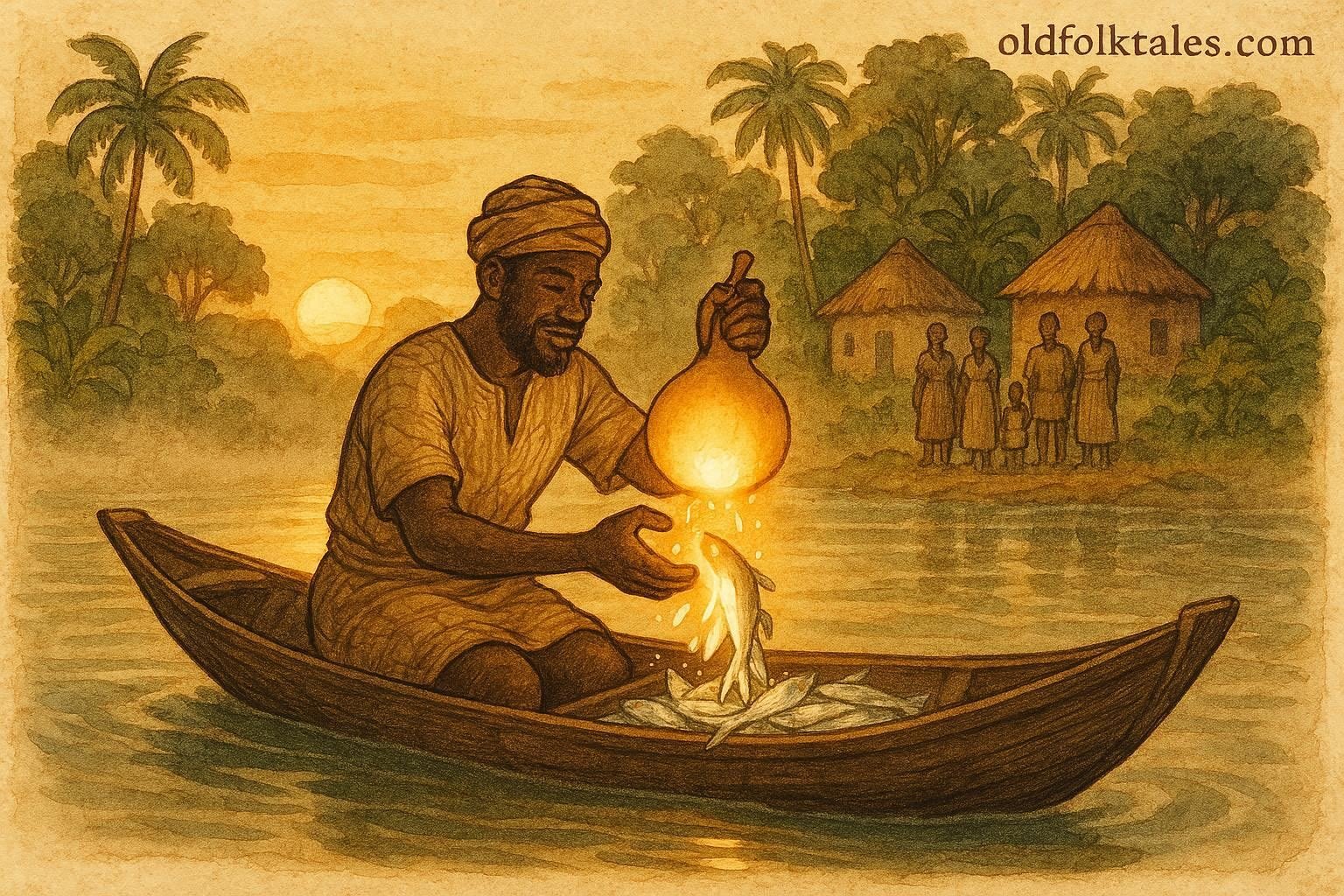

A breeze arrived, cool as a blessing. The gourd bottle tapped the canoe twice, as if to be noticed. Ayo reached for it, thinking, If a gourd wishes to speak, let it speak in daylight. He cracked the cowrie seal. The river paused. From inside rose a whisper, then a chorus, then the soft laugh of water against stones. A pulse of light spilled over his knees, and the canoe settled lower, heavy with silver flashes. Fish, big as a forearm, small as a thumb, flickered in the hull like scattered coins. The river opened its hand.

Ayo gasped, his heart rising like a drumbeat at a festival. He poled to shore and offered thanks, not loud, not proud, only steady, the way a man breathes when he understands that the world has noticed him. He remembered the elder’s warning and the weight of the child’s empty basket. He set aside a third of the fish, he wrapped them in banana leaves, and he carried them to the marketplace. He gave some to the yam seller, some to a woman whose baby’s eyes were tired, and some to the old drummer whose hands were swollen with age.

The news of the fisherman’s blessing walked faster than any feet. Some said Ayo had bargained with spirits. Some said he had charmed the river. When the chief’s steward came to ask for a “customary share,” Ayo bowed and offered a basket, but he did not boast about the gourd. At night he returned to the river, placed the gourd on the water, and said, If your goodness wants a home, let it be my heart, and if it needs to wander, let it wander free. The gourd bobbed twice, then drifted to the reeds and vanished.

Days passed. The fish kept coming, not in wild floods, but in faithful measure, enough for food, enough to share, enough to keep poverty from gnawing the doorway. The child and his mother brought Ayo roasted yam with palm oil, and the elder gifted him a small calabash carved with river symbols. When festival season arrived, Ayo paid the drummer to teach the children a song of gratitude. The song was simple, the rhythm like paddles, the words like a net that catches the light, thank you, river, for your patience, thank you, people, for your hands.

Years later, when Ayo’s hair held the color of cotton, children would ask, Baba, how did the river choose you. Ayo would smile, patience chooses patient people, and generosity returns to the hands that let go. The canoe is small, the river is big, and kindness is the only paddle that never splinters.

Moral, True fortune arrives where patience and generosity already live

Author’s Note, Yoruba riverside communities hold deep respect for water as living presence, so this version centers the river’s agency and the communal logic of sharing. The blessing is not a jackpot, it is a steady flow that matches the rhythm of kindness. I leaned on the proverb style of elder speech, and on marketplace reciprocity, to foreground how wealth becomes meaningful only when it circles back to the village.

Knowledge Check

Theme, What two virtues unlock Ayo’s blessing, answer, Patience and generosity

Symbol, What does the gourd represent, answer, Sacred potential that responds to character

Setting, Which river landscape shapes events, answer, A Yoruba riverside community on the Ogun River

Conflict, What problem tests Ayo before the blessing, answer, Emptiness of his nets and the crying child’s lost yams

Resolution, How is wealth distributed, answer, Ayo shares fish with families, the market, and elders

Takeaway, What tool never splinters in Ayo’s words, answer, Kindness

Origin, Yoruba, Nigeria