In the early days, the tree called Loko was like any other in the forests of Tendjñ. Its branches stretched high, and its leaves whispered secrets with the wind. There lived a poor man named Kakpo, known for his skill in making hoe handles. Day after day, he ventured into the bush to cut trees for wood, hoping to earn a modest living.

One day, Kakpo discovered a sturdy tree, perfect for his craft. He lifted his axe to strike, but a voice stopped him. “Do not cut me down,” said the tree. “No man must cut me down.”

The tree, Loko, was no ordinary tree. Within it lived three vodun: Da, Dangbe, and the toh Myo of the Ayato clan. Loko’s spirit shone through its bark, and its presence was both powerful and sacred.

Seeing Kakpo’s honesty, Loko made a proposal. “Turn your back to me,” the tree instructed. “If I grant you wealth, will you obey my commands?”

Kakpo, humble and eager, agreed. “Yes,” he said.

Loko then gave him seven small double calabashes, saying, “Take these. Find a good place, and break one on the ground. If I give you riches, will you honor your promise and offer me an ox each year?”

Kakpo accepted the calabashes and followed Loko’s guidance. When he broke the first, the spot became sacred. Breaking the second calabash summoned many houses. The third created walls around them. The fourth brought hammocks and stools fit for a king. The fifth filled the houses with people. The sixth made horses appear, and Kakpo rode one proudly. When he broke the seventh, he discovered Fa and Legba themselves, not mere symbols of worship, standing among him.

Through these wonders, Kakpo became king, ruler over wealth and people alike. Yet in his heart, greed overcame his honor. He failed to give Loko the ox he had promised.

Loko, displeased, transformed into a man, wrapped in raffia cloth, and approached Kakpo’s home to ask for water. The Minga, Kakpo’s servant, pushed him away. Undeterred, Loko returned. The Minga, unaware of the tree’s power, struck him with a whip. Loko left, then returned a third time. Again, the villagers, working for the chief, beat him.

This time, Loko began to sing:

“Pa down the hoes,

Come at once, and dance for me,

You dancers who dance well.”

The song carried magic. Instantly, all the villagers vanished, leaving Kakpo alone. His riches, his subjects, and even his horses disappeared. All that remained was the raffia cloth wrapped around him.

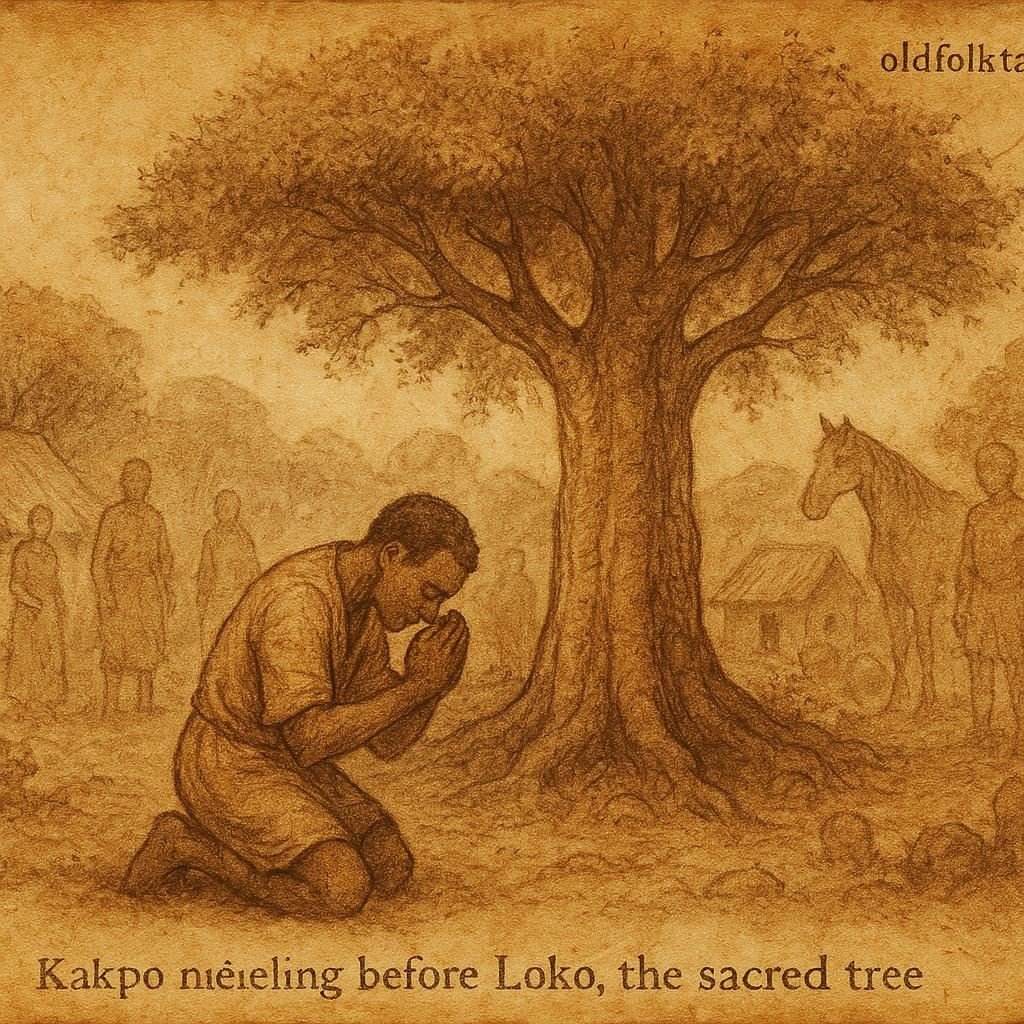

Kakpo pleaded, bowing to the sacred tree, dust upon his forehead. “Forgive me,” he begged. “I will give you the ox I promised.”

But Loko, steadfast, refused. Kakpo had broken a sacred vow, and for this disobedience, he lost everything. From that day onward, among the black people, some live in poverty, a reminder that promises to the vodun must always be kept.

Moral Lesson

This story teaches that promises to the sacred and divine must be honored. Disobedience brings misfortune, and even wealth cannot shield one from the consequences of broken vows.

Knowledge Check

Who was Kakpo in the folktale?

A poor man who made hoe handles and later became king.

What was Loko and why was it sacred?

A tree inhabited by three vodun—Da, Dangbe, and the toh Myo—making it sacred.

What did the seven calabashes represent?

Each calabash revealed wealth, structures, people, animals, and finally, Fa and Legba.

Why did Kakpo lose his wealth?

He broke his promise to Loko by not offering the yearly ox.

What magical effect did Loko’s song have?

It caused all villagers and wealth to vanish instantly.

What cultural lesson does this folktale teach?

Promises to the vodun must be honored; disobedience leads to misfortune and poverty.

Source: Beninese Folktale