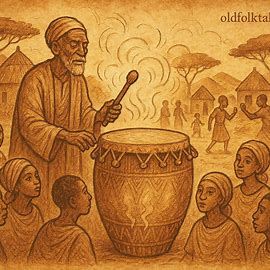

In the days when all the creatures of the forest lived together in harmony and sought the wisdom of those skilled in ancient crafts, there was a great mystery that puzzled the animal kingdom. Deep in the heart of the African wilderness, where the sound of hammering metal rang out across the savanna, stood the forge of Asanze the Shrike, a master blacksmith whose reputation for fine work had spread throughout the land.

The forge was a marvel to behold, with its great stone hearth glowing red-hot from dawn until dusk, and the rhythmic pounding of hammer against anvil creating a music that called to creatures from villages far and wide. Sparks flew like tiny stars in the smoky air, and the acrid scent of heated metal mingled with the earthy smells of the African bush. Asanze, despite his small stature, commanded respect from all who came to his workshop, for his skill was unmatched and his tools were sought after by hunters, farmers, and craftsmen alike.

Every morning, as the sun painted the eastern sky in brilliant shades of orange and gold, animals would arrive at the forge to have their tools sharpened, their weapons repaired, or new implements crafted for their various trades. They came from every corner of the territory: Njaba the Civet with his distinctive spotted coat, Uhingi the Genet with her elegant striped tail, Edubu the Snake gliding silently through the grass, and many others, each bringing work that required the blacksmith’s expert touch.

Also read: The Hunter and Bwinge

But there was a peculiar custom that had developed around these daily visits to the forge, one that had created a puzzle so confounding that it threatened to disrupt the harmonious working relationship between the animals and their trusted blacksmith.

Each day, when the work was completed and the last tool had been hammered into shape, the animals would perform a ritual that had become as regular as the sunrise itself. They would carefully gather all their newly crafted or repaired implements and place them in a neat pile on the ground outside the forge, creating what appeared to be a collection of abandoned tools but was actually a deliberate challenge.

Before departing for their respective homes, the animals would approach Asanze with a question that had become the source of endless frustration for the skilled bird. “Show us which among us is the eldest,” they would demand, their voices carrying a mixture of curiosity and challenge. “If you can solve this riddle and determine our true ages, then you may return our tools to us. But if you cannot, they remain here as testimony to your failure.”

Day after day, Asanze would study the assembled creatures with his keen blacksmith’s eye, the same careful attention he brought to examining metal for flaws or impurities. He would look at their faces, searching for signs of age in their features. He would observe their movements, hoping to detect the telltale slowness that might come with advanced years. He would listen to their voices for the tremor or roughness that time might have brought.

But to his growing dismay, the animals appeared to be remarkably similar in age. Their coats were equally glossy, their movements equally sure, and their voices equally strong. There were no obvious grey whiskers to indicate seniority, no stooped postures to suggest the weight of many seasons, no clouded eyes to reveal the passage of countless moons.

Each evening, as the shadows lengthened and the forge fire dimmed to glowing embers, the animals would depart empty-handed, leaving their tools behind as a mounting testament to the puzzle that seemed impossible to solve. The pile grew larger with each passing day, and Asanze’s reputation as a wise creature began to suffer under the weight of his inability to answer this seemingly simple question.

It was during this period of mounting frustration that Kudu the Tortoise, who had long been a friend and confidant of the blacksmith, decided to offer his assistance. Tortoise was known throughout the region for his cleverness and his ability to see solutions where others saw only problems. His shell bore the wisdom-marks of many seasons, and his slow, methodical approach to challenges often revealed insights that escaped faster, more impulsive minds.

“My friend,” Tortoise said to Asanze one morning as he arrived at the forge, “I believe I can help you solve this riddle that has been troubling you so greatly. Allow me to work the bellows for you today, and I will show you a method that reveals what the eyes cannot see.”

Asanze, desperate for any solution to his dilemma, readily agreed to his friend’s offer. As Tortoise settled himself beside the great leather bellows, he also began preparing something that initially puzzled the blacksmith: three carefully wrapped bundles of food, each containing different types of meat prepared in the traditional style of their people.

The first bundle contained the rich, fatty meat of Njaba the Civet, combined with the tender entrails of a red antelope. The aroma that rose from this package was complex and sophisticated, with layers of flavor that spoke to experienced palates and mature tastes.

The second bundle held the lean, delicate meat of Uhingi the Genet, prepared simply but expertly to preserve its subtle natural flavors. This was food for those who had moved beyond the intensity of youth but had not yet reached the refined preferences of true elderhood.

The third and final bundle contained the meat of Edubu the Snake, prepared in a way that emphasized its novelty and excitement rather than its complexity. This was fare that would appeal to the adventurous spirits and unsophisticated palates of the very young.

As the day progressed and Tortoise worked the bellows with steady, practiced movements, the other animals arrived as usual to continue their various projects at the forge. The familiar sounds of hammering and shaping filled the air, punctuated by the rhythmic whoosh of air being forced into the flames by Tortoise’s careful work.

When the sun reached its peak and hunger began to stir in the bellies of the workers, Tortoise rose from his position at the bellows and announced that he had prepared refreshments for everyone. He unwrapped the first bundle with deliberate ceremony, allowing the rich aroma to drift across the workshop.

“Come forward, those who would enjoy this jomba of Njaba with the finest entrails,” he called out, using the traditional term for the wrapped food bundles that were common in their culture.

Without hesitation, several of the animals stepped forward eagerly, their eyes bright with anticipation as they caught the complex scent of the offering. They divided the rich meal among themselves, savoring each bite with the appreciation that came from palates trained by many seasons of varied experience.

Next, Tortoise unwrapped the second bundle, its more subtle aroma creating a different kind of appeal. “Come forward now, those who would enjoy this jomba of Uhingi,” he announced.

Again, a group of animals responded, though different individuals than those who had chosen the first offering. They accepted their portions with evident pleasure, their selections revealing preferences that fell between the extremes of complexity and simplicity.

Finally, Tortoise presented the third bundle, its exotic and straightforward appeal immediately attracting the attention of the remaining animals. “And now, come forward, those who would enjoy this jomba of Edubu,” he declared.

The youngest animals in the group responded enthusiastically, drawn by the novelty and the uncomplicated appeal of the snake meat, which required no sophisticated palate to appreciate.

As the meal concluded and the animals returned to their work, Tortoise observed with satisfaction that his experiment had succeeded beyond his expectations. The preferences revealed by the food choices had created clear groups that corresponded exactly to the age distinctions that physical appearance had failed to reveal.

When the day’s work was finally completed and the familiar ritual began once again, with the tools being placed on the ground and the challenge being issued to determine relative ages, Asanze was ready with an answer that would finally solve the mystery.

However, recognizing that his friend Tortoise deserved credit for the solution, the blacksmith deferred to the clever reptile, asking him to announce the decision as if it were the bird’s own wisdom being revealed.

Tortoise cleared his throat with the gravity befitting such a momentous occasion and addressed the assembled animals with the authority of one who had solved an ancient puzzle through careful observation and clever insight.

“The solution has been revealed through the choices you yourselves have made,” he announced solemnly. “Those among you who chose to eat the jomba of Njaba with its rich complexity are the eldest, for only mature palates appreciate such sophisticated flavors. Those who selected the jomba of Uhingi represent the middle years, drawn to food that balances simplicity with substance. And those who eagerly consumed the jomba of Edubu are the youngest, for the young are always attracted to novelty and straightforward pleasures.”

The animals looked at one another with expressions of wonder and recognition, seeing the truth of the assessment reflected in their own choices. The logic was undeniable, and the method of determination was both fair and clever.

With unanimous agreement, they acknowledged the accuracy of Tortoise’s pronouncement and gratefully collected their tools, finally ending the daily ritual that had puzzled them all for so many moons.

Moral Lesson

This folktale teaches us that wisdom often lies in understanding that appearances can be deceiving, and that true insight comes from observing behavior and preferences rather than relying solely on physical characteristics. It shows how creative thinking and careful observation can solve problems that seem impossible through conventional methods.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who was the blacksmith in this African wisdom tale, and what daily challenge did he face? A: Asanze the Shrike was the blacksmith who faced the daily challenge of determining which animals were eldest among his customers, who would leave their tools behind until he could solve this puzzle.

Q2: How did Tortoise help solve the age puzzle that confounded the blacksmith? A: Tortoise prepared three different food bundles with varying complexity of flavors, rich Civet with antelope entrails, simple Genet meat, and novel Snake meat, then observed which animals chose which foods based on their taste preferences.

Q3: What did the food choices reveal about the animals’ ages? A: The animals who chose the complex Civet dish were the eldest (mature palates), those who selected the Genet meat were middle-aged (balanced tastes), and those who picked the Snake meat were youngest (attracted to novelty and simplicity).

Q4: What African cultural element is represented by the “jomba” food bundles? A: The jomba represents the traditional African practice of wrapping and preparing food in bundles, demonstrating how cultural food customs can reveal deeper truths about preferences and characteristics.

Q5: Why couldn’t physical appearance determine the animals’ relative ages? A: All the animals appeared to be of similar age physically, they had equally glossy coats, sure movements, and strong voices, with no obvious signs like grey whiskers or stooped postures to indicate seniority.

Q6: What does this folktale teach about problem-solving and wisdom? A: The story demonstrates that creative approaches and behavioral observation can solve problems that conventional methods cannot, showing that wisdom lies in understanding hidden patterns rather than relying on obvious appearances.