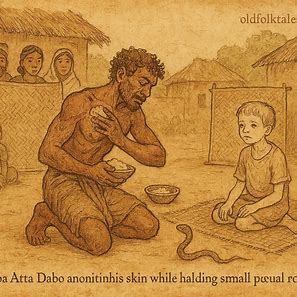

My name is Samba Atta Dabo, and I am the one who cares for those whom sorcerers have made ill. If evil has been done to a person, it is I who cures him. When I wish to turn away troubles sent by wicked hands, on Monday and on Thursday I anoint my skin with a medicinal powder and prepare myself; that is how I can see the sorcerers. Before they go into the village they must pass by my house and ask my leave. They pronounce magical words upon entering so I cannot hold them, but I for my part pronounce others which prevent them from leaving. These words I cannot reveal to you; they are forbidden.

I practise my art from my compound among mud houses and low palms, where neighbours gather at dusk. If a sorcerer disobeys my orders and does harm or trouble the country, I take the victim from his hands and repair the evil done. The work asks for steady hands, a steady voice, and patience for things that creep at the edge of sight.

Last year, at Thievaly, a sorcerer afflicted the daughter of the diaraf Samoro. All Diolof knew of it; the child lay pale and trembling, and no ordinary cure would ease her. They called Mabadiane, a bourhama famed for facing sorcerers. He arrived, pronounced three words, and spat into the little girl’s ear. For a moment she rose, but then spat back, accusing him of taking presents from sorcerers and of robbing people. He owned the shame.

READ: Old Fatou and the Jinn | A Gambian Folktale

Sara Bouri of Yang-Yanga came next and tried two words and a spit; she rejected him too, declaring him weaker than Mabadiane. Galdiol of M’Boula tried and failed. They brought the child to Yang-Yang to Fara Thianor’s house and fetched a Laobe from M’Ballarhe, but each visitor met the child’s derision: “You have no cure for me,” she said. The village grew anxious as the little one’s strength waned.

When all others failed, they sent for me. At first, I refused: why call me after those believed stronger had acted? They answered that if I cured her everyone would know who was truly the greatest bourhama of the country. Moved by their plea, I consented and went straight to Fara Thianor’s courtyard.

As I entered the hut the child started and declared that someone had just come whom she dreaded. I rubbed my skin with many medicines, crushed roots, bitter ash, and oils that smell of earth, and held her. I spoke two commanding words and spat into her ear. She cried aloud that everyone had tried and failed. I told her I was not like the others: the sorcerer had taken her heart and hidden it in the rheteurh.

Surprised, she asked how I knew and in what the sorcerer had placed it. I answered plainly: on a shard of pot with a dog’s heart, the heart of a goat, and a piece of cavatt. I pronounced other secret words, spat again, and then asked what payment would be given when she was cured. She named thirty francs to start and seventy-five after recovery.

She described the medicine in detail: the root of nguer from Rhorondom’s house, to be dried and powdered; a root of ngotot from the little house of the marhmarh; a piece of serao wood to finish it. If I prepared this triple remedy as she instructed, she said, she would be cured.

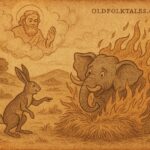

I ordered the sorcerer to be summoned and commanded him to bring back what he had taken. The child warned he would refuse and hide his work. I threw my medicines into the fire and watched the smoke rise as I invoked him. She told me where he moved, behind the Residence, at Moussa Sal’s, at Fara Dienguel’s, and on his way to Goumbo Mata Niang. I bade him not to go to and fro but to come.

The child revealed that the sorcerer had hidden the vital thing in the burrow of a goat’s hindquarters. When he arrived, he tried to lay it in her hands; I forbade it and ordered that it be placed upon her head. I commanded him to wash his right hand and pour the water over the child’s head; he did so, and then rinsed his mouth and sprinkled that water as ancient law requires.

He attempted to shift blame, saying his rhambeu was at his brother’s place, yet I called him to fetch it. I warned that if he pronounced certain words the serpent would come, and scarcely had I spoken than the serpent appeared. Women cried out, some wept aloud, and the mother bent over her child.

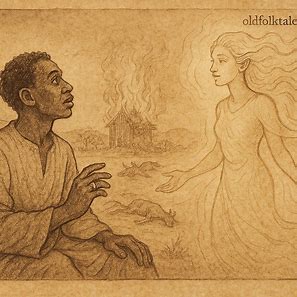

I prepared the remedy as the child had told me: the powdered roots and wood combined; a small draught offered at the right moment. I fed this to the child. Slowly her breathing steadied, color returned to her cheeks, and the spell began to break. At last, she rose, clear-eyed and whole.

Her parents paid the agreed seventy-five francs, and news of the cure spread from Thievaly to Diolof and beyond. After that day, many came first to my threshold when sorcery troubled them, for they had seen that calm skill joined to precise rites could undo the dark work of envy and magic. Thus, the country recognized me as a great bourhama. From then on, the people came with faith, bringing offerings and stories of the cure to tell.

Moral Lesson

True power over harm is not simply in secret words or showy rites but in steady hands, humility, and method. The tale shows that a healer’s authority grows from calm skill, careful practice, and a willingness to face what others will not. It also warns that trust, once shaken by greed or shame, must be restored by clear deeds, not words alone.

Knowledge Check

- Who is Samba Atta Dabo in this Wolof folktale?

Samba Atta Dabo is the bourhama (exorcist/healer) who cures those harmed by sorcery. - What ritual practice lets Samba see sorcerers?

He anoints his skin with medicinal powder on Mondays and Thursdays to perceive sorcerers. - Where did the afflicted girl live and who was her father?

The girl was from Thievaly and was the daughter of the diaraf Samoro. - What did the child say the sorcerer had hidden her heart in?

She said the sorcerer hid her heart on a pot shard with a dog’s heart, a goat’s heart, and a piece of cavatt. - What three ingredients composed the cure the child described?

Root of nguer (from Rhorondom’s house), root of ngotot (from the marhmarh’s house), and serao wood, powdered and combined. - What cultural role does the bourhama play in Wolof communities?

A bourhama is a respected healer/exorcist who uses ritual, herbal knowledge, and secrecy to protect and restore families against sorcery.

Source: Wolof Folktale, The Gambia, West Africa. Recorded by Samba Atta Dabo; published in Wolof Stories from Senegambia (ed. David P. Gamble, Gambian Studies No. 10, 1987), originally collected from earlier published sources including F.-V. Équilbecq, Contes Indigènes de l’Ouest-Africain Français (1915).