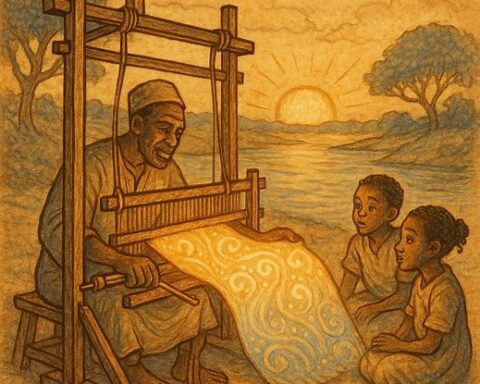

Long ago, in the forests of Equatorial Guinea, the animals lived close to one another, their villages forming a vast, lively town. It was a place of constant chatter, where birds sang from tree to tree, monkeys swung across branches, and the ground shook with the movement of beasts both great and small. Among these animals were two neighbors: Yongolokodi the Chameleon, known for his slow steps and cautious ways, and Ko the Wild Rat, whose quick wit and sharp nose often got him both into and out of trouble.

Seasons shifted, and one year brought hardship. The rains had been unkind, and food was scarce. Hunger gnawed at the bellies of all creatures, from the smallest squirrel to the mighty elephant. Yet, as though to restore balance, the following season yielded a harvest of astonishing abundance. The forests overflowed with ripe fruits, nuts, and roots. Trees bent under the weight of their produce, and the air was sweet with the smell of ripening harvests. The animals could not gather it all, for the fruitage was more than their paws, claws, and jaws could manage.

Chameleon, delighted by the sight, made his way to Ko’s home. His slow steps carried him with measured care until he reached the burrow of his friend. “Chum, Ko!” Chameleon said, his voice bubbling with joy. “This harvest is a great thing! Look at the bounty the earth has given us!”

But Ko, twitching his whiskers nervously, shook his head. “Do not speak of it, Yongolokodi. Do not let your tongue betray us. The more we boast, the greater the danger. Let us enjoy this quietly.”

Chameleon promised silence, but word travels faster than footsteps. Mankind, ever watchful, had overheard whispers of the forest feast. Hunters gathered, sharpening their arrows and setting their snares. Soon the once-peaceful town of beasts was filled with the terrifying sounds of ambush. Bows twanged, guns thundered, and the metallic snap of traps echoed through the forest. Screams and cries of startled animals filled the air.

Amid the chaos, Ko the Wild Rat scurried frantically. His tiny paws moved swiftly, but fate was cruel. A hidden snare caught him with a sharp snap, ku! He writhed and squealed, trapped and helpless.

Chameleon, who had been nearby, watched his friend’s struggle. Yet instead of rushing to help, he puffed out his chest and said with self-righteous pride, “Ko, remember, it was you who warned me not to speak of the harvest. And I obeyed. I did not tell anyone. I am not the cause of this misfortune.”

His words were cold, offering no comfort. Ko struggled in vain, hearing his friend’s defense instead of his aid. Chameleon, more concerned with proving his innocence than saving a friend, stood aside as hunters approached. The once-glorious abundance had turned into a tragedy, and blame hung heavier than fruit on the branches.

The animals scattered, some escaping with scars, others falling prey to the traps of men. But in that moment, what echoed longest in memory was not the sound of Ko’s squeals, nor the hunter’s weapons, but Chameleon’s words: “Not my fault!”

Moral of the Story

This folktale from Equatorial Guinea teaches that silence and obedience to advice are not enough when true loyalty is tested. Friendship demands responsibility, and in times of crisis, excuses are no substitute for action. Blame-shifting may protect pride, but it destroys trust. The story warns us that those who care only about avoiding fault may end up losing the very bonds that give life meaning. True friendship requires courage, sacrifice, and accountability.

Knowledge Check

Who are the main characters in the folktale?

Yongolokodi the Chameleon and Ko the Wild Rat.

What event triggered the arrival of hunters?

The abundance of food, which attracted many animals and drew the attention of men.

What trap did Ko fall into?

He was caught in a snare set by hunters.

What lesson does Chameleon’s behavior teach?

That shifting blame and avoiding responsibility destroy trust and loyalty in friendships.

Why did Ko warn Chameleon not to speak of the harvest?

Because boasting might attract danger from hunters or men.

What is the cultural origin of this folktale?

It is an Equatorial Guinean folktale.

Source: Equatorial Guinean folktale.