Long ago, in the bustling village of Calabar where the Cross River met the Atlantic Ocean and palm wine flowed freely at evening gatherings, there lived a chief whose compound was the grandest in all the land. The walls were built of red clay bricks that gleamed in the tropical sun, and the courtyard was shaded by massive palm trees whose fronds whispered ancient secrets in the coastal breeze.

Within this prestigious household lived the chief’s daughter, Nkoyo, a girl whose beauty was matched only by her stubborn spirit. Her dark eyes sparkled with mischief, and her elaborate cornrow hairstyles were adorned with cowrie shells that clicked softly as she moved through the compound with the confidence of one born to privilege. Nkoyo had grown up hearing the constant sound of “yes” to her every whim, and her willful nature had earned her a reputation throughout Calabar as “the mischievous girl.”

The village elders would shake their gray heads whenever they saw her, their weathered faces creased with knowing smiles as they watched her latest antics unfold. “That child,” they would mutter over their palm wine, “has the spirit of a hurricane trapped in a calabash. One day it will either destroy everything or bring great fortune.”

Also read: The Moonlight and Sunlight

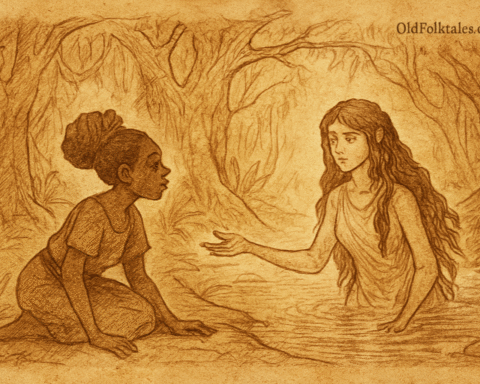

In the same grand compound, but occupying a very different position, lived a servant girl named Anwa. She had been brought from a distant town when she was barely old enough to carry water pots, her family having fallen on hard times during a particularly harsh drought. Unlike the pampered chief’s daughter, Anwa had learned to navigate the world through observation, patience, and an intelligence that sparkled like sunlight on river water.

Her hands were skilled at weaving baskets from palm fronds, her voice could soothe crying babies with traditional lullabies, and her mind worked like the intricate gears of a master craftsman’s creation. Though their social stations were as different as the earth and sky, something magical happened between the two girls, they became the closest of companions, sharing whispered secrets under the starlit African sky and dissolving into fits of laughter that echoed through the compound walls.

One dry season, when the harmattan winds carried dust from the distant Sahara and the air shimmered with heat, the chief received an important summons. A great meeting of regional leaders was to be held in a neighboring village, and his presence was required for matters of trade, marriage alliances, and territorial agreements that could affect their community for generations.

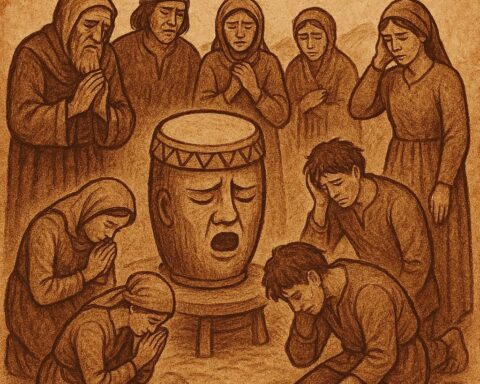

Before departing with his wife in a procession befitting their status, accompanied by drummers, praise singers, and gift bearers, the chief gathered his household. His voice carried the authority of generations of leadership as he addressed the two girls who stood before him in the main courtyard.

“The compound will be locked during our absence,” he declared, his elaborate agbada robes rustling in the morning breeze. “You must remain inside these walls until we return. Behave yourselves, and above all, do not go looking for trouble.” His stern gaze lingered particularly on his daughter, whose reputation for finding mischief was well known throughout the household.

For the first day after their departure, the compound felt strangely quiet. Nkoyo wandered from room to room like a caged bird, her usual energy dampened by the restrictions placed upon her. She sulked on woven mats, picked at her elaborate jewelry, and complained to anyone who would listen, which, in this case, was only Anwa.

But as the sun climbed higher and the day grew warmer, a more pressing concern emerged. Nkoyo’s stomach began to rumble with increasing urgency, and she realized that all the yam barns and food stores had been securely locked before her parents’ departure. The reality of their situation hit her like a splash of cold river water.

“Anwa!” she cried, her voice rising with panic. “What shall we eat? The yam barn is locked tight, and I am absolutely starving! My stomach feels as empty as a dried gourd!”

But Anwa simply smiled, her eyes twinkling with the kind of mischief that came from cleverness rather than recklessness. “Do not fear, my friend,” she said with quiet confidence. “I will find us food.”

As evening painted the sky in shades of orange and purple, Anwa slipped through a small gap in the compound fence that she had noticed during her daily chores. The village beyond was alive with the sounds and smells of evening preparation, cooking fires crackling, children laughing, and the rich aroma of traditional dishes filling the warm air.

She made her way directly to a food seller known throughout Calabar for her delicious ekpang nkukwo, a hearty dish of cocoyam and plantain wrapped in leafy vegetables, and pepper soup that could warm the soul on even the coldest harmattan night. The woman’s stall glowed invitingly in the flickering light of oil lamps, and steam rose from her cooking pots like incense offerings to the evening spirits.

With the quick wit that had served her well since childhood, Anwa spun a tale so convincing and delivered with such charm that the food seller found herself ladling generous portions into a clay pot. “My mistress will send payment tomorrow,” Anwa promised with the innocent sincerity that only the truly clever can master. “She is testing the quality of your famous cooking for a great feast she is planning.”

She returned to the compound carrying the steaming food like a triumphant hunter, and she and Nkoyo ate until their bellies were satisfied and their laughter echoed through the empty courtyard.

Day after day, Anwa repeated her clever expeditions, each time with a different story, a new approach, a fresh angle that kept the food seller interested and generous. Sometimes she used charm, batting her eyes and complimenting the woman’s cooking skills. Other times she employed laughter, telling jokes that made the seller forget about payment in her amusement. And sometimes she made elaborate promises about future business that sounded so profitable the seller couldn’t refuse.

Nkoyo watched these performances with growing delight, clapping her hands and marveling at her friend’s boldness. “You are more clever than Anansi the spider!” she would exclaim, referring to the legendary trickster of West African folklore.

But after many days of this routine, the food seller’s patience finally wore thin. Her suspicions had been growing like storm clouds on the horizon, and her anger simmered like pepper soup left too long on the fire. “This little girl has made a fool of me for far too long,” she muttered to herself, grinding pepper with extra force. “Today I will teach her a lesson she will never forget.”

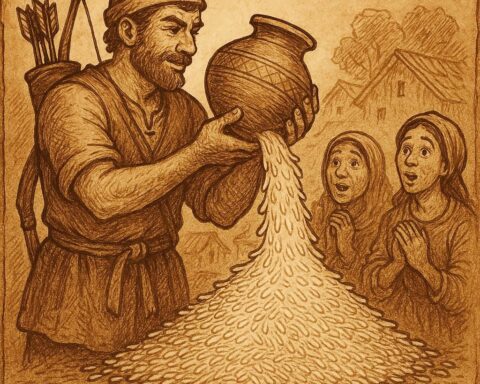

She prepared a dish so loaded with fiery pepper that it could have awakened the ancestors themselves. The soup burned like liquid fire, and even the steam rising from it was enough to make grown men weep.

But when Anwa arrived for her daily visit, her sharp eyes immediately detected the trap. Without missing a beat, she pretended to taste the impossibly spicy food with pure joy, smacking her lips theatrically and declaring it the sweetest, most delicious meal she had ever encountered.

The food seller stared in complete shock as this small girl appeared to devour the burning soup with genuine pleasure, praising its flavor so convincingly that the woman began to doubt her own cooking skills. Thoroughly confused and somewhat impressed despite herself, she found herself sending Anwa home with yet another pot of properly prepared food.

When the chief and his wife finally returned from their important meeting, their procession announced by the beating of traditional drums and the joyful ululations of the household servants, they expected to find two hungry, perhaps somewhat chastened girls. Instead, they discovered Nkoyo and Anwa healthy, glowing, and full of barely contained laughter.

“How did you manage to survive and even thrive without us?” the chief asked, his eyebrows raised in amazement as he looked at his daughter’s bright, mischievous smile.

Nkoyo, despite all her faults, possessed one admirable quality, she was never jealous of her friend’s abilities. Pointing proudly at Anwa, she declared with genuine admiration, “It was Anwa who kept us alive with her incredible cleverness. Without her wit and courage, we would surely have starved!”

Moral Lesson

True friendship transcends social boundaries, and intelligence combined with loyalty can overcome any obstacle. While mischief for its own sake can lead to trouble, when guided by wisdom and genuine care for others, even the most daring schemes can lead to survival and success. Sometimes the greatest treasures are found not in wealth or status, but in the cleverness and devotion of a true friend.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who are the main characters in this Nigerian folktale from Calabar? A1: The main characters are Nkoyo, a spoiled chief’s daughter known as “the mischievous girl,” and Anwa, a clever servant girl from a distant town. Despite their different social positions, they become close friends who support each other.

Q2: What challenge did the girls face when left alone in the compound? A2: When Nkoyo’s parents locked the compound and traveled to another village, the girls were trapped inside with no access to food since all the yam barns and food stores were locked. They faced potential starvation during their parents’ absence.

Q3: How did Anwa solve the problem of getting food for herself and Nkoyo? A3: Anwa cleverly slipped out through a gap in the fence and repeatedly tricked a local food seller into giving them ekpang nkukwo and pepper soup by using different charming stories, wit, and promises of future payment from her “mistress.”

Q4: What was the food seller’s plan to catch Anwa, and how did she outwit it? A4: The angry food seller prepared an impossibly spicy pepper soup to teach Anwa a lesson. However, Anwa detected the trap and pretended to enjoy the fiery dish, praising it as the sweetest meal she’d ever tasted, which confused the seller into giving her proper food.

Q5: What does this folktale reveal about friendship across social classes in Nigerian culture? A5: The story shows that true friendship can transcend social boundaries between a chief’s daughter and a servant girl. It demonstrates that mutual respect, loyalty, and complementary strengths (Nkoyo’s privilege and Anwa’s cleverness) can create powerful bonds.

Q6: What lesson does this Calabar folktale teach about intelligence and resourcefulness? A6: The tale teaches that wit, creativity, and courage can overcome seemingly impossible obstacles. It shows that intelligence and loyalty are more valuable than social status, and that clever thinking combined with friendship can turn potential disaster into triumph.

Source: Nigerian folktale, Calabar region