In a small village where children gathered for learning, there lived a kind and dedicated teacher named Goso. Unlike other teachers who instructed their pupils in enclosed schoolhouses, Goso held his lessons beneath the spreading branches of a magnificent calabash tree. The tree provided cool shade during the hot afternoons, and its generous canopy created a perfect outdoor classroom where knowledge flowed as freely as the breeze.

One peaceful evening, as the sun began its descent toward the horizon, Goso sat alone under his beloved tree, preparing the next day’s lessons with great care. The village had grown quiet, and the teacher was so absorbed in his work that he noticed nothing unusual, not even the slight rustling in the branches above his head.

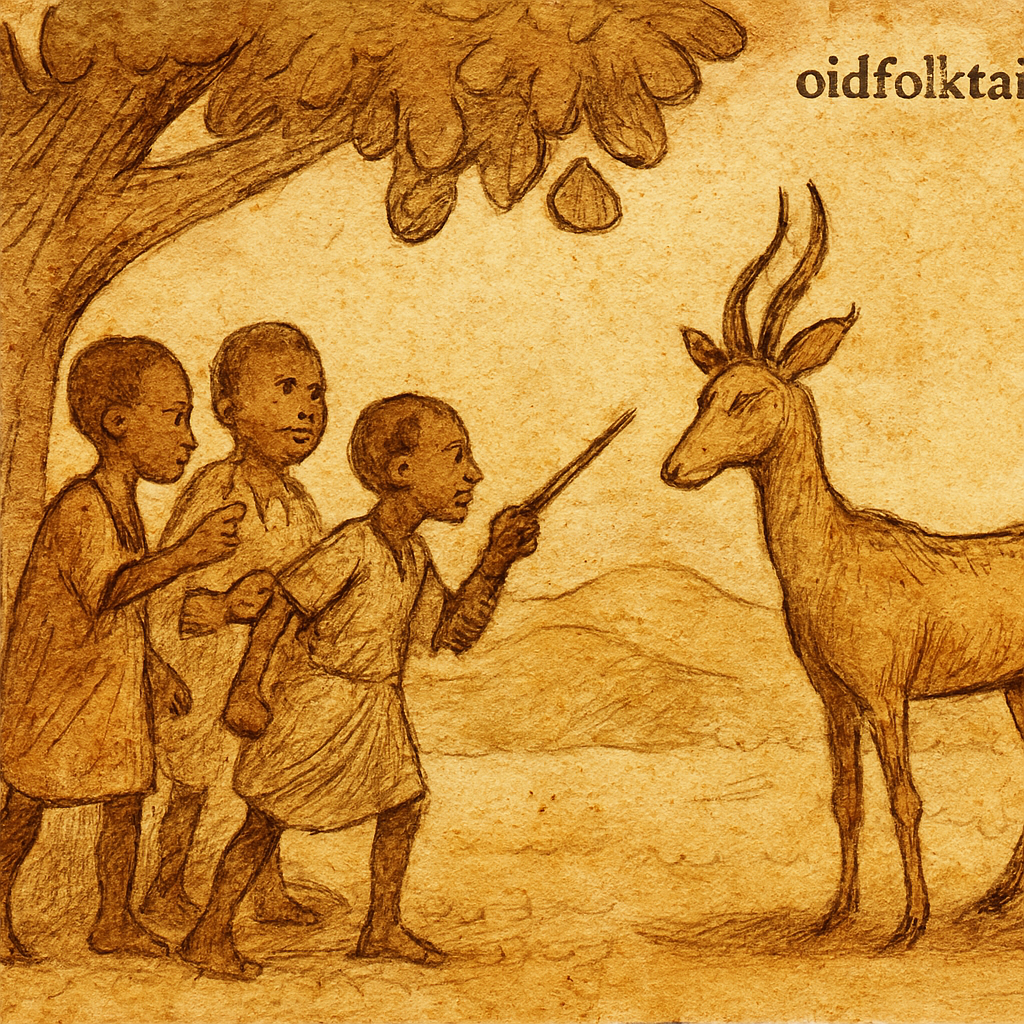

High up in the calabash tree, Paa the gazelle had climbed silently, his eyes fixed on the ripe fruit hanging temptingly from the branches. The gazelle was a cunning thief, and he moved with practiced stealth, reaching for the choicest calabashes. But in his greed and haste, Paa’s hoof struck a heavy calabash, dislodging it from its stem. The fruit plummeted downward like a stone, striking Teacher Goso squarely on the head with a terrible crack. The beloved teacher fell instantly, his life extinguished in a single tragic moment.

Click here to discover more legendary tales from West Africa

When morning came and the students arrived for their lessons, chattering and eager to learn, they found a sight that filled their hearts with unbearable sorrow. Their teacher lay motionless beneath the tree, his teaching materials scattered around him, never to be used again. The children wept bitterly, their grief echoing through the village.

After giving Goso a proper and respectful burial, the students gathered in a solemn circle. Their sadness transformed into fierce determination. “We must find whoever killed our teacher,” they declared with one voice, “and bring them to justice!”

The students examined the scene carefully, noting the fallen calabash beside their teacher’s body. They reasoned together and concluded that Koosee, the south wind, must have blown the calabash from the tree. Filled with righteous anger, they pursued the wind, captured it, and began to beat it.

“Stop! I am Koosee, the south wind!” it cried out. “Why do you strike me? What wrong have I done?”

“You threw down the calabash that killed our teacher Goso,” the students accused. “You should not have done such a terrible thing!”

But Koosee protested, “If I were truly so powerful, could I be stopped by a simple mud wall?”

The logic struck the students as sound, so they turned their attention to Keeyambaaza, the mud wall, and beat it instead.

“Wait! I am Keeyambaaza, the mud wall!” it protested. “Why do you beat me? What is my crime?”

“You stopped Koosee, the south wind, who threw down the calabash that killed Teacher Goso,” they explained.

But the wall replied, “If I were so mighty, could I be bored through by a tiny rat?”

And so the students pursued Paanya, the rat, catching and beating it. The rat cried out its innocence, pointing to Paaka, the cat, who hunted it. The cat, in turn, blamed Kaamba, the rope, that tied it. The rope blamed Keesoo, the knife, that cut it. The knife blamed Moto, the fire, that burned it. The fire blamed Maajee, the water, that extinguished it. The water blamed Ng’ombay, the ox, that drank it. The ox blamed Eenzee, the fly, that tormented it.

Each creature and element the students encountered added to the growing chain of their quest. With each confrontation, they recited the entire sequence, their voices creating a rhythmic chant that grew longer and longer: “You torment the ox, who drinks the water, that puts out the fire, that burns the knife, that cuts the rope, that ties the cat, who eats the rat, who bores through the wall, which stopped the wind, and the wind threw down the calabash that killed our teacher!”

Finally, the fly revealed the final link: “If I were so powerful, would I be eaten by the gazelle?”

The students’ eyes widened with understanding. They searched the village and the surrounding wilderness until they found Paa, the gazelle, and dragged him before their tribunal. They beat him and recited the entire chain of causation, their voices trembling with emotion as they reached the end of their long journey.

But when they finished, something unexpected happened. Paa the gazelle stood before them in stunned silence. The surprise of being discovered, combined with the crushing guilt of having accidentally killed the teacher while engaged in his shameful theft, struck him completely dumb. No clever excuse came to his lips, no deflection of blame, no protest of innocence. He simply stood there, unable to speak.

The students looked at one another with grim satisfaction. “Ah!” they said. “He has not a single word to say in his own defense. This is truly the one who threw down the calabash that struck our beloved Teacher Goso. Justice demands his life.”

And so, beneath the same calabash tree where their teacher had died, the students executed Paa the gazelle, bringing their long quest for justice to its final, unavoidable conclusion. The death of Teacher Goso had been avenged.

The Moral of the Story

This powerful tale teaches us about accountability and the interconnected nature of actions and consequences. While the students follow a long chain of causes, each element correctly identifies something more powerful than itself, until they reach the true source, the gazelle whose greedy theft set everything in motion. The story reminds us that even accidental harm caused by wrongdoing must be answered for, and that we cannot escape responsibility by blaming the circumstances that enabled our actions. Justice may follow a winding path, but it ultimately finds its target. The tale also illustrates how every action ripples outward, affecting others in ways we might not anticipate.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who was Teacher Goso and what made his teaching unique?

A: Teacher Goso was a dedicated educator who taught children to read under a calabash tree rather than in a traditional schoolhouse. This outdoor classroom setting made him beloved by his students and connected learning with nature, making his tragic death even more poignant to his pupils.

Q2: What is the significance of the chain structure in this Ivorian folktale?

A: The chain structure, where each element blames something more powerful, creates a cumulative tale that teaches about interconnection and cause-and-effect. It demonstrates how actions are linked together and emphasizes the importance of finding the root cause rather than blaming intermediary factors. This repetitive pattern is common in West African oral storytelling traditions.

Q3: Why couldn’t any of the elements (wind, wall, rat, cat, etc.) be held responsible for Goso’s death?

A: Each element correctly argued that if it were truly powerful, it would not be overcome by the next thing in the chain. The wind is stopped by walls, walls are bored by rats, rats are eaten by cats, and so on. This logical progression shows that none of them was the initiating force they were merely parts of a natural order exploited by the gazelle’s deliberate action.

Q4: What does the gazelle’s silence represent in the story?

A: Paa the gazelle’s inability to speak represents guilt and the impossibility of denying ultimate responsibility. Unlike all the other elements that could point to something more powerful, the gazelle had no excuse his theft directly caused the teacher’s death. His silence symbolizes the weight of undeniable culpability and the shame of being caught in wrongdoing.

Q5: What lesson does this folktale teach about justice and accountability?

A: The story teaches that true justice requires finding the actual source of harm, not just the immediate cause. While many factors contributed to the tragedy, only the gazelle bore moral responsibility because his intentional theft set the fatal chain in motion. The tale emphasizes that we cannot escape accountability for harm caused by our wrongful actions, even if the harm was accidental.

Q6: Why is the calabash tree important to this Ivorian tale’s cultural context?

A: The calabash tree is significant in Ivorian and West African culture, providing both food and materials for daily life. Its use as a teaching location reflects traditional outdoor education practices in Côte d’Ivoire. The fact that a calabash typically a symbol of sustenance and utility, becomes the instrument of death creates tragic irony, showing how even beneficial things can cause harm when misused or disturbed by wrongdoing.

Source: Ivorian folktale, Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast), West Africa