In the lush landscapes of Guinea-Bissau, where the tropical winds carried the scent of rich earth and distant ocean, there lived a hardworking man who tended a beautiful garden with great care and devotion. This garden was his pride, but its most precious treasure was a magnificent fig tree that belonged to his beloved son. The tree stood tall and proud, its broad leaves offering shade while its branches promised sweet, green figs that would ripen under the warm African sun.

Each morning, the father would rise early to tend to his work in the distant fields, leaving his young son with a sacred responsibility. “Watch over your fig tree, my boy,” he would say with gentle authority. “Guard it well, for it is yours to protect and nurture.”

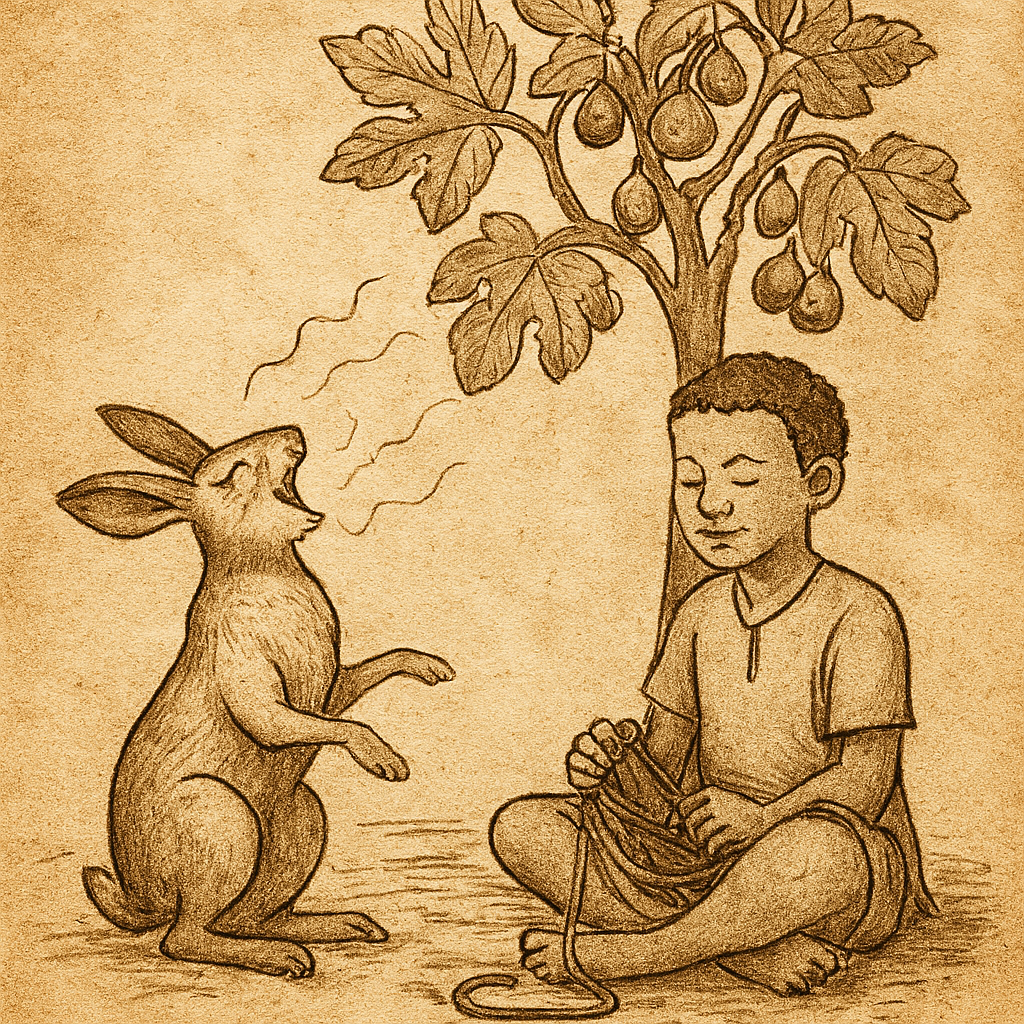

The son, filled with the earnest dedication that only children possess, would settle himself near the precious tree, his eyes alert for any sign of danger. But what the boy did not know was that a cunning hare, known in the local Creole tongue as lebri, had been observing this daily ritual with growing interest.

Also read: The Trickster Hare and the Bean Garden

This hare was no ordinary creature. It possessed a voice so melodious and enchanting that it could charm the birds from the trees and lull the wariest soul into a trance. Hidden among the shadows of the surrounding trees, the hare would watch and wait for the perfect moment to execute its clever plan.

One fateful morning, as the father disappeared over the horizon to begin his day’s labor, the hare emerged from its hiding place. The pape (father) was barely out of sight when the magical creature began its bewitching performance. Its voice rose like liquid honey in the morning air, weaving a song so beautiful and hypnotic that it seemed to make the very leaves dance in rhythm.

“Your father will come, so your child will eat that green fig tree,” the hare sang in the most melodious tones imaginable, the words flowing like a gentle stream over smooth stones. The song seemed to speak directly to the boy’s heart, filling him with an inexplicable sense of permission and even duty.

The child, completely entranced by the sweet melody, felt his vigilance melting away like morning mist. Without fully understanding why, he found himself rising to fetch cord and rope, as if responding to some ancient, irresistible call. The hare’s song had woven a spell around his innocent mind, making the impossible seem not only reasonable but necessary.

With the boy thoroughly enchanted, the hare approached the precious fig tree and began its feast. It ate with the enthusiasm of one who had planned this moment for days, savoring each sweet, green fig as the hours passed. The creature gorged itself from sunrise until the golden light of evening painted the sky in shades of amber and rose.

As darkness began to fall, the satisfied hare turned to the still-mesmerized child and spoke a single word: “Dismancan” a local expression meaning it was time to go. The child, suddenly snapping out of his trance, became alarmed as awareness flooded back. The hare bounded away into the gathering night, leaving behind a trail of destruction and a bewildered boy.

The next day brought the same enchanting performance. The hare’s song seemed even sweeter, more irresistible than before. The boy woke from his normal state of alertness even more readily, and the cunning creature ate and ate until completely satisfied before departing with another casual “dismancan.”

This pattern continued day after day, with the hare growing bolder and the fig tree suffering greater damage with each visit. The boy, caught in the spell of that magical voice, seemed powerless to resist the daily deception.

Finally, the father returned to inspect his garden and check on his son’s guardianship. His heart sank as he surveyed the devastation wreaked upon the precious fig tree. Branches hung stripped and broken, and the ground was littered with the remains of what should have been a bountiful harvest.

“Anton,” the father called to his son, using a name that carried both affection and growing concern, “are you properly watching over this side of the garden?”

At that moment, a wolf happened to be passing nearby, drawn by some unknown instinct to this place of unfolding drama. The ever-opportunistic hare, seeing a chance to escape consequences once again, called out sweetly, “Dismancan, for I will be gone to play (marau).”

The wolf, not understanding the context but sensing some kind of invitation or command, became alarmed (dismancal) and remained nearby. The satisfied hare, believing it had once again cleverly avoided responsibility, bounded away to continue its games.

But the father, his weathered face clouded with understanding and righteous anger, finally grasped the full scope of the deception that had been played upon his innocent son.

“Ah!” he declared, his voice trembling with controlled fury, “it is you who have been tricking my son, making him leave his post so you could feast upon our green figs!”

The father, consumed with rage at the violation of trust and the theft of his son’s precious fruit, seized a heavy iron tool from his work supplies. In his anger and confusion, mistaking the innocent wolf for the guilty party, he began to strike the bewildered animal. The wolf, caught completely off guard and unable to understand this sudden violence, could not defend itself properly.

Strike after strike fell upon the unfortunate wolf until it seemed to succumb to the relentless assault. But just as the last breath seemed to leave the creature’s body, the hare suddenly appeared from its hiding place, perhaps moved by some unexpected pang of conscience.

“No!” the hare cried out, “I will save him from death!”

But it was too late. The damage had been done, and the tragic consequence of the hare’s deception had claimed an innocent life.

Later, as the full truth finally emerged through questioning, the child asked his father with confused tears in his eyes, “But father, did you order the hare to come and eat from our tree?”

“No, my son!” the father replied firmly, “I never ordered the hare to come and eat from our fig tree.”

“But the hare said that you ordered it to come and eat,” the boy protested, his innocence shining through his confusion.

“No! Tomorrow, when it comes again, you must be ready and alert. Whoever tells you to be alarmed or to leave your post, don’t be alarmed and don’t leave until I return,” the father instructed, finally understanding how his son had been so thoroughly deceived.

The story ends with the hare’s recognition that its clever tricks, while successful in achieving its immediate desires, had led to consequences far more serious and tragic than it had ever intended.

Moral Lesson

This Guinea-Bissauan folktale teaches us that deception, no matter how cleverly executed or sweetly presented, inevitably leads to unintended and often tragic consequences. The hare’s beautiful song and cunning words achieved its immediate goal of obtaining the figs, but resulted in the death of an innocent wolf who became caught up in the web of lies. The story reminds us that our actions affect not just our intended targets, but can harm completely innocent parties who happen to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Knowledge Check

Q1: What role does the hare’s singing play in this Guinea-Bissauan folktale? A: The hare’s enchanting song serves as the primary tool of deception, hypnotizing the boy into abandoning his duty to guard the fig tree. The melodious voice represents how manipulation can be disguised as something beautiful and appealing.

Q2: What does the fig tree symbolize in this Guinea-Bissauan story? A: The fig tree represents responsibility, inheritance, and the trust between father and son. As the boy’s special tree, it symbolizes his coming of age and the importance of protecting what has been entrusted to one’s care.

Q3: How does the character of Anton represent innocence in the story? A: Anton embodies childlike trust and innocence, showing how young people can be easily deceived by those who exploit their trusting nature. His character demonstrates the vulnerability of the innocent to manipulation.

Q4: What cultural elements make this distinctly Guinea-Bissauan? A: The story uses Guinea-Bissauan Creole terms like “lebri” (hare), “pape” (father), “dismancan” (go/leave), and “marau” (play), reflecting the unique linguistic heritage of Guinea-Bissau’s blend of African and Portuguese cultures.

Q5: Why does the innocent wolf become a victim in this folktale? A: The wolf’s tragic fate illustrates how deception creates chaos that often harms completely innocent parties. The wolf represents collateral damage from the hare’s lies, showing how trickery spreads consequences beyond the original participants.

Q6: What lesson does the father’s final instruction teach about vigilance? A: The father’s warning to stay alert and not be swayed by anyone telling the boy to abandon his post teaches the importance of maintaining responsibility even when faced with persuasive arguments or apparent authority.

Source: Guinea-Bissauan folktale