There was once a girl who lived under a stepmother’s roof with no mother or father to protect her; small of frame and plain of face, she could neither hoe nor cook the way other village girls could, and every day she was given work while they walked off to be marked and celebrated for womanhood. Her stepmother kept her always at hand with chores: fetch water before dawn, grind millet at the pestle until her arms ached, and stir porridge late into the night. She obeyed without argument, hoping that one day she, too, might be allowed to join the others in the rite of marking.

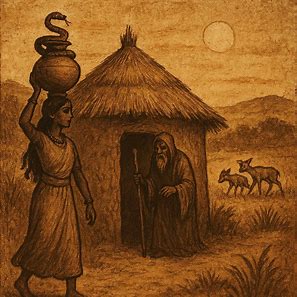

One afternoon, when the other girls had gone to the doctor and the sun leaned to the west, the girl slipped away and followed a different track through the bush. She was thirsty and tired and, turning a bend, found a tiny hut made of bent twigs and thatch. An old woman opened the door and offered a cup of water on a single condition, empty the pot, then fetch water from the river beyond the monkey-fruit trees and return to meet her. The old woman said she was a doctor; to the girl’s surprise she also promised to do the marking herself.

Hungry for the rite and for the company of the others, the girl agreed. The old woman put a coil on her head, not a rope but a living snake, wound as neatly as a basket rim. The girl shuddered, but a little mongoose that lived in the hut chirped and nudged the snake, and the beast lay quiet like a harmless ring. The girl took the coil and walked the long bush road to the river. She filled the pot, cooked the porridge the witch-doctor had instructed, and ate until the hunger thinned. That evening the old woman bade her climb to the loft to sleep, warning that the woman’s son, who returned late from hunting, might otherwise mistake her for a meal.

In the dark hours the son returned and smelled the scent of cooking. He climbed toward the loft to seize what he could, but the household, strange companions indeed, rose to guard the child. The snake about the tub lashed and wrapped the son’s legs; the mongoose bit his hand; a rat nipped his heels; a wild cat screeched and leapt. Pots fell, grain spilled, a pot of salt crashed and mixed with the meal. The son, surprised and wounded, was beaten and bound by the old woman until dawn.

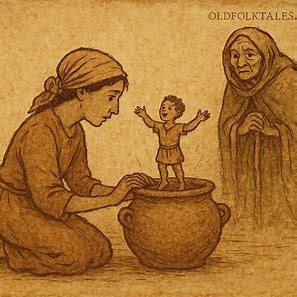

At sunrise the old woman drew a tiny knife and notched the girl’s two upper front teeth, placing a paste of herbs into the gaps and laying a cool charm in her mouth. “Keep your lips shut until you pass the village border,” she said. “Do not speak of the medicines. Keep secret what you have been given.” The girl did as bid and walked home with a cautious joy.

When she came into the village, she found the other girls already marked and the people gathered. Her stepmother, who had tried to bar her from the rite, stood with a face like a stone. The villagers urged the girl to open her mouth to show the notch; at first, she hesitated, then obeyed. From her mouth poured not words but a marvel: first one cow, then another and another; goats and fowls tumbled out as if she had been a living storehouse. Each animal swelled into life as it hit the ground, flesh and hoof brightening, eyes opening and sound breaking into the air. Herds formed where none had been.

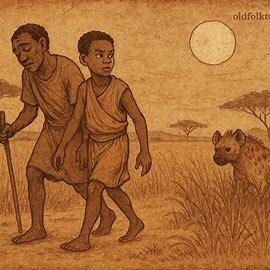

READ: Singambala and Kabwell: Heroes of the Hunt | A Tale from Zambia

A hush fell and then a roar of joy: the village, once short of beasts and food, would no longer go hungry. The stepmother’s cruelty was exposed for the smallness it was, and the villagers turned to the girl with gratitude and a new respect. They lifted her up and asked her to be leader of the homesteads and protector of this sudden bounty. They clothed her, they fed her, and they called her chieftainess. Where once she had been ignored and cruelly tasked, she now sat with elders.

Before long people from other hamlets came to ask where such magic might be learned. They found only the empty hut of the old woman; the snake, the mongoose, the rat and the cat slipped quietly back to the bush. The miracle could not be purchased or copied. It had come as reward for the girl’s patience, her willingness to do the hard and strange tasks asked of her, and her courage in the face of fear. Thus, the plain child was transformed into a leader: from scorned labourer to mother of her own people. The elders retold the tale for years, of the coil of snake upon her head, of the loft where she sat above a would-be cannibal’s rudeness, and of the animals that guarded her, so that every child who heard it would learn that endurance, humility in hardship, and performing the tasks set before you can change a fate and turn small kindnesses into great blessings. Her name was remembered for the grace with which she bore her trials.

Moral Lesson

This tale teaches that patient endurance and courage in obedience to difficult tasks may yield unexpected abundance. It also offers a warning: cruelty and petty jealousy toward the vulnerable can be overturned, while acts of strange kindness, no matter the hand that offers them, may change a life and a community.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who helped the girl complete the rite and what did she ask in return?

A1: An old woman who was both a diviner and witch-doctor; she asked the girl to fetch water and to sleep in the loft for the night.

Q2: Which small animals guarded the girl during the night?

A2: A snake (used as a coil), a mongoose, a rat, and a wild cat helped defend her.

Q3: What physical marking showed the girl had been through the rite?

A3: Two small notches were removed from her upper front teeth, filled with medicinal paste.

Q4: What miraculous event occurred when the girl opened her mouth in the village?

A4: She vomited cattle, goats and fowls that became full-grown animals, seeding a new settlement.

Q5: How does the story frame the stepmother’s behaviour in relation to the girl’s reward?

A5: The stepmother’s attempts to prevent the girl from the rite are shown as small cruelty that is overturned by fate and the girl’s eventual elevation.

Q6: Which people’s tradition does this story belong to?

A6: The Ramba people of Zambia.

Source: Ramba folktale, Zambia. Collected in Folktales of Zambia (see: Chiman L. Vyas, comp., “Folktales of Zambia” collection).