Once, long ago in the highlands of Guinea, where the fog kisses the tops of the Fouta Djallon mountains and the rivers whisper to the rocks, there lived a girl named Niala. She was not like the other children of her village. While they played, danced, and laughed under the sun, Niala sat beneath trees, eyes closed, listening—not to people, but to birds. She listened so intently that she could imitate their calls better than the finest flutist in the village. People said she was odd, maybe even cursed. But her grandmother, Yaye, knew better.

“She has the gift,” Yaye would whisper to anyone who’d listen. “She understands more than we do.”

Niala was raised by her grandmother, a respected herbalist and storyteller. Her parents had died when she was still in the womb—taken by a fever that swept through the valley. Niala was born in sorrow but grew in peace, cradled in love by the woman who taught her to listen to the wind, to watch the way leaves danced, and most of all, to listen to the birds.

Each morning, before the rooster crowed, Niala would wander into the forest with a calabash of water and a pouch of millet. She would sit beneath the tall silk-cotton tree and sprinkle the seeds on the ground. The birds came in flocks: blue-breasted rollers, firefinches, hornbills, and weaverbirds. They chirped, cawed, trilled, and squawked. To the villagers, it was just noise. But to Niala, it was language—poems written in the air.

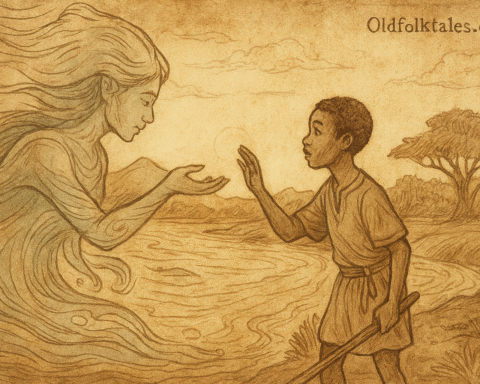

One morning, as the mist still wrapped the forest like a shawl, a black bird with glowing yellow eyes landed in front of Niala. She had never seen this kind before. It looked at her not as a bird looks at a human, but as an equal. It opened its beak and said, “Niala, child of wind and root, danger comes to your people.”

Startled, she almost dropped her calabash. “You speak!” she whispered.

“I do, as do all my kin. You hear because your spirit listens. You understand because your heart remembers.” The bird’s voice was not screechy, not soft, but clear—like a flute cutting through silence.

“What danger?” she asked.

“A drought is coming. Not a drought of rain, but a drought of hearts. Your chief has struck a deal with the foreign miners who come with greed in their eyes. They will poison the river. The fish will die. The forest will fall. The birds will fly away. The spirits will be silent. Unless you act.”

Niala ran back to the village, her feet skipping over stones and roots. She found her grandmother grinding baobab leaves.

“Yaye, I spoke with a bird. A real bird! He warned me.”

Yaye smiled, not surprised. “The time has come, then. You must speak to the elders.”

“But they won’t listen to a girl!”

“They might not. But the forest will.”

With Yaye’s blessing, Niala went to the village square during the council’s gathering. The chief sat on his carved stool, draped in indigo robes. Around him sat the elders, each older than the river, it seemed. Niala stepped forward.

“I have a message,” she said, voice trembling. “A message from the forest.”

They chuckled. One elder leaned on his staff and said, “Child, this is not the time for riddles.”

“I am not joking. The river will be poisoned. The fish will die. The trees will fall. And you—” she looked at the chief, “you are the one who will open the gate.”

Silence fell. Then the chief rose. “You dare accuse me? Based on bird-chatter and dreams?”

“I heard it with my ears. The birds speak. The forest cries.”

The crowd murmured. Some scoffed. Others looked uneasy. But the chief waved his hand. “Enough. Go play with your feathers.”

That night, Niala did not cry. She walked back to the forest and sat beneath the silk-cotton tree.

“Birds of the air,” she whispered, “help me.”

The forest stirred. Then came the voices—not just of one bird, but dozens. Together they spoke: “Then we will show them.”

The next morning, the village awoke to silence. Not a single bird sang. No rooster crowed. No pigeon fluttered. It was as if the sky had stopped breathing.

Then came the smell—something foul. The river had turned dark. Fish floated belly-up. The villagers gathered in fear.

Then, like an army, the birds returned—but not with songs. They cried in alarm, flying low over the village, circling the council hut.

The people began to whisper: “Niala was right. The forest is angry.”

The chief came out, his face pale. A foreign truck had crashed near the riverbank the night before. Fuel had leaked into the water. It was true. Everything was true.

Niala was summoned.

She stood tall, her voice steady. “You see now. You didn’t hear the birds because your hearts were too full of power and greed. But now, maybe, you’ll listen.”

The elders bowed their heads. The chief, ashamed, stepped down from his seat. A new council was formed—one that included the voices of women, of youth, of wisdom. And Niala was named Guardian of the Forest.

From then on, decisions were made with care. The river was cleansed with the help of the spirits, the miners were banished, and the birds returned—not only in flocks but in spirit. Songs filled the sky once more.

And every morning, beneath the silk-cotton tree, Niala still sat. But now, beside her sat children, old women, hunters, and farmers, all learning what it meant to truly listen.

✧ Commentary

This Guinean folktale highlights the deep spiritual relationship between humans and nature. Niala’s story teaches that wisdom does not always come with age or status. It is a tale of environmental awareness, female strength, and ancestral connection. The forest, birds, and rivers are not background elements—they are active participants in the community. The story reflects West African oral traditions where nature speaks, and only the truly attentive can understand its warnings.

✧ Moral

Those who listen with humility will hear what the world is trying to say, even when others ignore it.

✧ Questions & Answers

1. Q: Who was Niala, and what made her special? A: Niala was a young girl who could understand the language of birds and was deeply connected to nature.

2. Q: What warning did the black bird give Niala? A: It warned her that the village chief had made a deal with miners who would poison the river and destroy the forest.

3. Q: How did the villagers react when Niala tried to warn them? A: Most mocked her, and the chief dismissed her warnings, refusing to believe a young girl.

4. Q: What convinced the villagers that Niala was telling the truth? A: The river turned black, fish died, and the birds returned crying loudly, confirming the bird’s prophecy.

5. Q: What changes were made in the village after the disaster? A: The chief stepped down, a new council was formed including youth and women, and Niala was made Guardian of the Forest.