Gather close, children of the earth. Let the wind carry these old words to your hearts. Listen to the story that the grandmother moon whispered to the first people when the world was still learning its name…

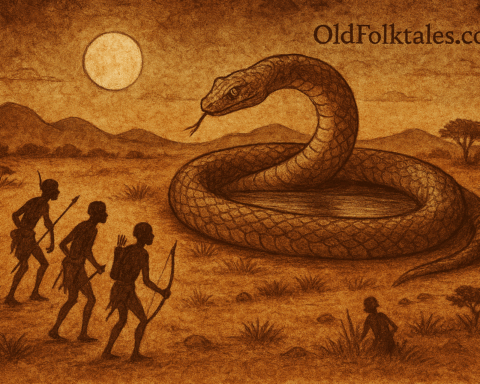

In the time when the rains forgot to fall and the great thirst came to the Kalahari, there lived among the Kung people a girl child named Nai-ka-tara, She-Who-Walks-Silently. Small, small she was, like a young springbok, but her eyes held the depth of ancient waterholes, and her heartbeat with the rhythm of the old songs.

The drought, ai, the drought. It stretched across the land like a great yellow beast, swallowing rivers, cracking the earth, turning the green places to dust and thorns. The game animals wandered far, far away seeking water. The people grew thin as shadows, their water gourds empty, their bellies singing the hunger song.

But worse than the thirst, worse than the hunger, came the lions.

A great pride had moved into the territory, driven from their own lands by the same cruel dryness. Seven lionesses strong and fierce, led by a scarred male whose roar shook the baobab trees. They had claimed the last waterhole the sacred pool that had never run dry, not in the memory of the oldest grandmother.

“We cannot reach the water,” said the headman, his voice cracked like dry leather. “The lions guard it day and night. If we approach, they will tear us like grass dolls.”

The hunters tried, oh, they tried! With their poison arrows and clever traps, with fire brands and loud shouting. But the lions were desperate too, and desperate lions are dangerous as lightning storms. Three hunters came back bleeding. Two did not come back at all.

The people held counsel under the dying moon. Some said, “We must leave this place, find new lands.” Others said, “We must fight, drive out the lions or die trying.” But the old ones, the wise ones, shook their heads sadly.

“Lions were here before us,” they said. “Lions will be here after us. This is their way, as drought is drought’s way. We cannot blame the river for flowing or the wind for blowing.”

Little Nai-ka-tara listened, listened with her whole being. And in the deep quiet of her heart, she heard something else a voice like honey and thunder, like moonlight on still water.

“Child of the desert,” the voice whispered, “would you learn the old language? Would you speak the words that all creatures know?”

Nai-ka-tara was not afraid, for she recognized the voice. It belonged to the Great Mother, she who was the first woman, she who taught the people to make fire and gather veldkos, she who knew the name of every star.

“Yes, Grandmother,” she whispered back. “Teach me.”

That night, while her people slept fitfully, Nai-ka-tara crept from her shelter. The Great Mother’s spirit came to her in dreams and visions, pouring the ancient knowledge into her young mind like water into a gourd. She learned the lion-speech, the deep rumbling words that spoke of pride and territory, of family and survival. She learned the courtesy-songs, the greeting-calls, the peace-making sounds that said: “I come in respect, I come in understanding.”

When the sun rose red and angry, Nai-ka-tara walked toward the waterhole. Her mother cried out, her father tried to stop her, but she moved like one in a trance, guided by power older than human fear.

The lions saw her coming. The great male rose, his mane like a storm cloud around his mighty head. The lionesses tensed, ready to charge. But Nai-ka-tara did something no human had ever done she spoke to them in their own tongue.

“Great hunters,” she rumbled in the deep lion-speech, “I greet you. I see your strength. I honor your pride.”

The lions froze, ears pricked forward in amazement. A human child speaking the old language! The scarred male padded closer, his yellow eyes studying her with new interest.

Nai-ka-tara continued, her small voice carrying the ancient words: “I know your pain, brothers and sisters. The drought hurts you as it hurts us. Your cubs are thirsty. Your bellies ache with emptiness. But we are all children of the same desert, drinkers from the same sky.”

The lioness-mother, she who had lost two cubs to the terrible thirst, stepped forward. “Little human,” she purred, “you speak truth. But why should we share the water? We are many, we are strong.”

“Because” Nai-ka-tara, “we know things you do not know. We know where the gemsbok herds have gone. We know which plants hold water in their roots. We know the songs to call the rain. Share the water, and we will share the knowledge.”

For a long moment, the lions looked at each other. Then the great male spoke, his voice like distant thunder: “You are brave, little one. Brave and wise. We will try this sharing you speak of.”

And so it began the great cooperation. The lions allowed the people to drink at dawn and dusk, while the people led them to hidden game trails and secret water-roots. Nai-ka-tara became the voice between them, translating needs and agreements, settling disputes with words instead of claws and spears.

When the rains finally came dancing across the desert, when the water-holes filled again and the game returned, both lions and people were stronger than before. The great pride moved on to their original territory, but they carried with them a new understanding. And the people never forgot the girl who spoke the ancient tongue.

Years later, when N!ai-ka-tara had become a woman and a mother herself, other tribes would come seeking her wisdom. “How do we live with the elephants who eat our gardens?” they would ask. “How do we make peace with the leopards who take our goats?”

And she would teach them what the Great Mother had taught her that all creatures speak the same deep language of survival and respect, of fear and hope. She would show them how to listen, really listen, to the voices that sing beneath the sounds of roar and growl and trumpet call.

“Remember,” she would say, “we share this earth with all our relations. The lion is our brother, the elephant our sister. When we speak to them with respect, they may answer with understanding.”

Even now, when the wind whispers through the thornbush and the lion’s roar echoes across the desert, the old ones remember N!ai-ka-tara’s teaching. They know that courage is not the absence of fear, but the wisdom to speak when words can heal the world.

This is the story as it was told to me, as it was told to those who came before, as it will be told to the children walking tomorrow’s paths. May you carry its wisdom like water in the desert of your days.

The Teaching of the Lion Speaker: Bravery and Harmony with Animals

The tale of Nai-ka-tara reveals profound truths about the nature of true courage and humanity’s relationship with the animal world. The girl’s bravery was not the reckless fearlessness often celebrated in heroic tales, but rather the deeper courage of understanding the willingness to see beyond the immediate threat to the underlying needs and fears that drive all living beings.

Her story teaches us that genuine harmony with nature cannot be achieved through dominance or avoidance, but only through the difficult work of communication and mutual respect. Nai-ka-tara succeeded where the hunters failed because she approached the lions not as enemies to be defeated, but as fellow desert dwellers facing the same fundamental challenges of survival. This perspective shift from adversary to neighbor opened possibilities that force could never create.

The folktale emphasizes that true wisdom lies in recognizing our interconnectedness with all life. The drought affected both human and lion communities, and their survival was ultimately linked. By sharing knowledge and resources rather than hoarding them, both groups emerged stronger. This reflects the San understanding that the desert ecosystem thrives on cooperation and mutual aid rather than competition and conflict.

The story also highlights the power of respectful communication across differences. Nai-ka-tara learned to speak the lions’ language not to command them, but to understand their perspective and express her own with dignity. This teaches us that meaningful dialogue whether between species, cultures, or communities requires us to step outside our own viewpoint and genuinely listen to the other’s experience.

Finally, the tale suggests that the gifts we receive like Nai-ka-tara’s ability to speak with animals carry the responsibility to serve not just our own community, but the larger web of life. Her teaching that “we share this earth with all our relations” reminds us that true leadership involves building bridges of understanding that benefit all beings, creating a world where courage and compassion walk hand in hand.

Knowledge Check: Understanding San Animal Communication Folklore

Q1: How do San folktales portray the relationship between humans and wild animals? A: San folktales typically portray humans and animals as interconnected members of a shared ecosystem, emphasizing mutual respect rather than dominance. Stories like “The Girl Who Spoke with Lions” show animals as intelligent beings with their own needs, fears, and social structures. The San worldview sees humans as part of the natural community, not separate from or superior to other species, promoting coexistence through understanding and communication.

Q2: What role does animal communication play in traditional San culture and storytelling? A: Animal communication in San culture represents deep spiritual connection and ecological wisdom. Traditional San stories often feature characters who can speak with animals, symbolizing the ability to understand and respect different perspectives. This reflects the San people’s intimate knowledge of animal behavior, gained through generations of hunting and living closely with wildlife, and their belief that true survival depends on cooperation with rather than conquest of nature.

Q3: How do San drought stories reflect their desert survival wisdom and environmental knowledge? A: San drought stories, like the lion girl tale, showcase sophisticated understanding of desert ecology and survival strategies. These narratives typically emphasize resource sharing, knowledge of hidden water sources, animal behavior patterns, and the importance of community cooperation during harsh times. They reflect practical wisdom gained from thousands of years of sustainable living in challenging environments, teaching that survival depends on adaptation and mutual aid.

Q4: What spiritual and cultural significance do lions hold in San folklore and tradition? A: Lions in San folklore represent power, courage, and the wild spirit of Africa, but also embody the principle that strength must be balanced with wisdom. They are often portrayed as formidable but fair, dangerous yet honorable creatures who can be reasoned with when approached respectfully. Lions symbolize the untamed aspects of nature that humans must learn to live alongside, representing both the challenges and the majesty of the natural world.

Q5: How do San coming-of-age stories teach children about courage and responsibility? A: San coming-of-age stories typically define courage not as fearlessness, but as the wisdom to act responsibly for the community’s benefit. Tales like N!ai-ka-tara’s journey show young people receiving special gifts or knowledge that must be used to serve others. These stories teach that true maturity involves understanding one’s place in the larger web of relationships—with family, community, animals, and the land—and accepting the responsibilities that come with special abilities.

Q6: What conservation and environmental messages appear in traditional San animal tales? A: Traditional San animal tales consistently promote conservation through messages of respect, balance, and sustainable coexistence. Stories emphasize that humans and animals share limited resources and must cooperate for mutual survival. They teach that understanding animal behavior and needs leads to better outcomes than conflict or exploitation. These tales reflect ancient wisdom about living sustainably within ecosystem limits, promoting harmony rather than domination as the path to long-term survival.