In a small West African village where the sun painted golden shadows across thatched roofs and dust danced in the warm afternoon light, there lived a man whose reputation preceded him wherever he went. His name was Chebe, and throughout the community of several hundred souls, he was known for one unmistakable trait: his insatiable appetite and boundless greed.

Chebe’s “long throat,” as the villagers called it, was legendary. Every morsel of food that crossed his path, every delicious aroma that caught his attention, would inevitably find its way down his gullet. His gluttony was so extreme that once, a piece of bone became lodged in his throat, and were it not for the swift intervention of Agheyih, the village healer with his ancient wisdom and healing herbs, Chebe would have met his maker that very day.

The villagers often whispered among themselves, comparing Chebe to the old proverb that mocks those unfortunate souls who have scabies but no nails to scratch them, a man cursed with a problem but blessed with no solution. Yet in truth, Chebe was more fortunate than he deserved, for he had married a woman of extraordinary kindness and patience.

Also read: The Selfish Mother

Male, his wife, possessed a heart as vast as the savanna sky. She understood her husband’s voracious nature and never complained, instead choosing to show her love through abundance. Each day, she would prepare enormous quantities of food portions so generous that visitors might think she was cooking for ten hungry children rather than one grown man. Her wooden spoons stirred with love, her clay pots bubbled with generosity, and her hands worked tirelessly to satisfy her husband’s endless hunger.

One particular morning, as the roosters announced the dawn and the village began to stir with the day’s activities, Male prepared a special meal of meker dze those delicious black-eyed peas that were a staple of their people. The aroma filled their modest home as she carefully seasoned the dish, her movements practiced and graceful. Before departing for the fields where she would tend their crops under the blazing sun, she set the steaming pot before her husband, confident that it would sustain him until her return.

But Chebe’s appetite was as boundless as a leopard caught in a hunter’s trap for three long days, ravenous, desperate, and all-consuming. When he finished the generous portion his wife had prepared, his stomach still rumbled with dissatisfaction, echoing like thunder across an empty plain. His eyes, gleaming with selfish desire, fell upon his wife’s detene, her personal store of precious peas set aside for future meals.

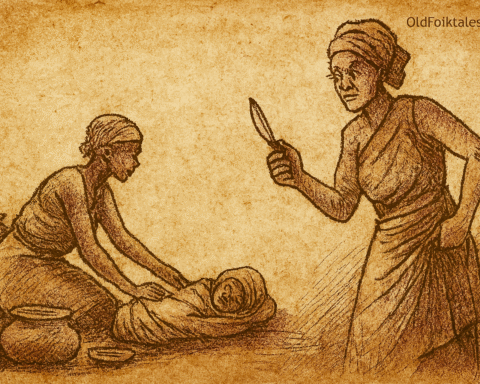

Without hesitation or shame, Chebe raided his wife’s supply. He filled another pot with the meker dze, watching the flames dance beneath it as the peas slowly cooked to perfection. The anticipation consumed him as surely as his greed consumed everything else in his path. When the peas were tender and ready, he carefully drained the cooking water and transferred them to a small aki, one of those rounded mortars that village women used for grinding spices and preparing special dishes.

With the devotion of a man preparing for a sacred ritual, Chebe seasoned his feast. He added salt until the crystals sparkled like tiny diamonds, sprinkled feleb with a generous hand, and ground hot pepper until his eyes watered from its potent fragrance. Then came the palm oil rich, golden, and abundant. He poured it over the beans with such lavishness that one might think he was preparing a wedding feast or celebrating the birth of a chief’s child.

But then Chebe committed an act so shocking, so contrary to the very fabric of village life, that the ancestors themselves must have shuddered in their eternal rest. In broad daylight, with the sun bearing witness to his shame, he closed his door. The wooden barrier that should have welcomed neighbors and friends instead shut out the world, creating a tomb of selfishness around his gluttony.

Dead-Father-of-Mine, what manner of man eats in secret when the sun shines bright? What human heart could be so hardened to the customs of sharing and community? Chebe pulled his chair close to the mortar, positioned himself like a king before his treasure, and began his solitary feast.

He ate with the determination of a man possessed. Each handful of seasoned peas disappeared down his throat as he watched his stomach expand like a drum being stretched for the harvest festival. The rounded pot of his belly grew larger and larger, pressing against his wrapper, straining the very limits of human capacity. Pain began to shoot through his bowels like lightning strikes, but still he would not stop.

Nothing would remain for visitors who might call. Nothing would be saved for his devoted wife upon her return from laboring in the fields. Most shamefully of all, nothing would be offered to the ancestors, those revered spirits who deserved the first portion of every meal according to the sacred traditions of their people.

Perhaps Chebe believed his stomach possessed the infinite capacity of Mother Earth herself for as the ancient wisdom teaches, the earth’s belly is never satisfied with the corpses it receives. But mortal flesh has its boundaries, and human stomachs have their limits, limits that Chebe was about to discover in the most tragic way possible.

As he continued his relentless consumption, oblivious to the approaching disaster, the inevitable occurred. Pwaaaaaaaaahhh! The sound echoed through the small house like a thunderclap as Chebe’s stomach exploded from the overwhelming burden he had forced upon it. All the food he had so greedily devoured came spilling back into the very aki from which he had eaten, a gruesome testament to his insatiable greed.

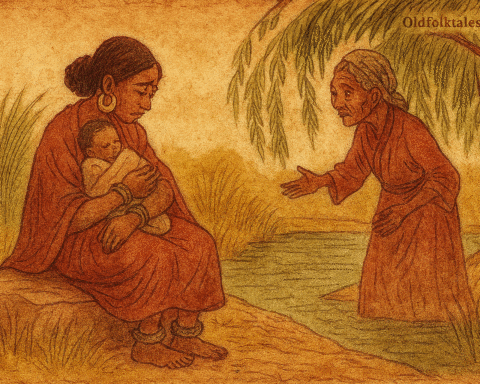

When Male returned from her day of honest labor in the fields, her hands still dirty from tending their crops, she was confronted with a sight that would haunt her for the rest of her days. Truly, as the old people say, it is only when the wind blows that the fowl’s anus is exposed and now the full extent of her husband’s shameful nature lay bare before her eyes.

The devoted wife stood frozen in the doorway, her mind struggling to comprehend the grotesque scene before her. Then, as grief and disbelief overwhelmed her heart, she began to weep. Her cries echoed through the village as she called upon her neighbors and ancestors, her voice rising in a mournful song that would be remembered for generations:

My husband is a glutton oh yang My husband is a glutton oh yang If I am the one, I eat and give you some, oh yang If you are the one, you eat and give me nothing My husband eats and dies, oh yang My husband eats and dies, oh yang When I eat, I share with you, oh yang When you eat, you do not share with me, oh yang

Her lament carried on the evening breeze, a testament to the ancient wisdom that teaches: the stomach of a stranger is like a small horn it cannot empty your granary. Male had lived her entire life according to this principle, always sharing, always giving, always considering others before herself. How could she have imagined that such a tragedy would unfold within her own home? How does a woman bear the shame of telling her community that her husband the man who shared her bed each night died not in battle or from illness, but from his own gluttony and selfishness?

Moral Lesson

This powerful folktale teaches us that greed and selfishness lead to self-destruction. Chebe’s inability to share, even with his devoted wife, ultimately caused his downfall. The story reminds us that moderation, generosity, and consideration for others are essential virtues. True satisfaction comes not from consuming everything for ourselves, but from sharing what we have with our community and honoring our relationships with gratitude and respect.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who was Chebe in this West African folktale? A1: Chebe was a villager known throughout his community for his extreme greed and insatiable appetite, often referred to as having a “long throat” due to his gluttony.

Q2: What role did Male play in the story and what did she represent? A2: Male was Chebe’s devoted wife who represented generosity and selflessness. She cooked large portions for her husband and embodied the traditional values of sharing and caring for others.

Q3: What is the significance of meker dze in this African folktale? A3: Meker dze (black-eyed peas) represents sustenance and abundance in West African culture. In the story, it becomes the instrument of Chebe’s downfall when his greed leads him to consume excessive amounts.

Q4: What cultural values does this folktale emphasize? A4: The story emphasizes traditional African values of sharing, community, hospitality, and honoring ancestors. It condemns selfishness and promotes the importance of generosity and moderation.

Q5: What is the symbolic meaning of Chebe closing his door while eating? A5: Closing the door symbolizes shutting out community, tradition, and the spirit of sharing that is fundamental to African village life. It represents the ultimate act of selfishness and isolation.

Q6: What lesson about greed does Chebe’s fate teach us? A6: Chebe’s explosive death teaches that extreme greed and selfishness are self-destructive. The story warns that those who consume without sharing or showing gratitude will ultimately face consequences for their actions.

Source: The sacred door and other stories, Cameroon folktales of the Beba (1st ed.). Ohio University Press.