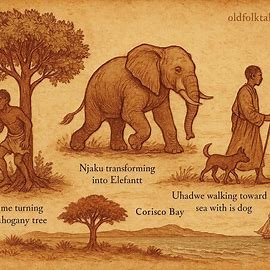

Long ago, on the shores of Corisco Bay in Equatorial Guinea, people spoke of a curious mark imprinted on a rock by the sea. It looked like the footprint of a man, though some insisted it was nothing more than a fossil. Yet, the elders told a tale, one that tied that print to the lives of three extraordinary brothers: Uhadwe, Bokume, and Njaku, sons of a mortal mother but bound to the will of Njambi the Creator.

The three brothers lived together until the day Uhadwe summoned them. “My brothers,” he said firmly, “the time has come for us to part. I shall go to the Great Sea. Bokume, you must take to the forest. Njaku, you too must find your place in the forest.”

Bokume obeyed without hesitation. He entered the deep, green forest, and there his body transformed. His form hardened, rooted, and rose into the towering trunk and wide canopy of the okume, the mahogany tree, beloved for its strength, shade, and value. Bokume became a guardian of the forest, a gift of wood for generations to come.

Njaku, however, was not so willing. Anger burned in his heart. “I will not hide in the forest,” he declared. “I will build and live among the townspeople.” With bold strides, he emerged from the trees, but his body began to change. His feet swelled grotesquely until they were massive and round like drums. His ears stretched and drooped down like great sails. His teeth grew into long ivory tusks, and his body grew enormous. He had become the first elephant.

READ MORE: The Leopard’s Marriage Journey: An Equatorial Guinean Folktale

The townspeople jeered and hooted at him, mocking his new form. Humiliated and furious, Njaku turned back toward the forest. Before disappearing into the trees, he thundered, “From this day, I will dwell in the forest, and whatever you plant there will perish by my hand. Your plantations and your food will be mine!” True to his word, the elephant became the terror of their farms, feeding on the people’s crops.

Meanwhile, Uhadwe journeyed toward the Great Sea. At the place where his feet touched the sand, a bush-rope sprang forth, winding its way across the ground. The staff in his hand transformed into a thick mangrove forest that spread along the water’s edge. Even his footprints, alongside those of his faithful dog, remained pressed into the rocks of Corisco Bay for generations to see.

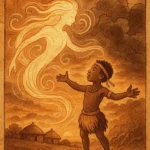

Uhadwe stretched out his power and created a sandbank across the ocean. By this path, he crossed into the Land of the Great Sea. There, he built a mighty ship and filled it with all the goods and treasures by which foreign men, especially white men, gained wealth. He then turned to his sailors and said, “Go and bring me my brother.”

The ship sailed across the waters until it anchored off the African coast. For four days, it remained untouched, for the people had no canoes to reach it. None dared to swim or wade through the waves.

At last, Uhadwe appeared in a dream to the townspeople. “Go to the forest,” he told them, “cut down the tree Bokume, the okume, and fashion a canoe from its trunk. With it, you may reach the ship.”

At dawn, the villagers obeyed. They felled a great mahogany tree, hollowed it into shape, and launched it onto the waves. Four young men were chosen to paddle out. Fear gripped them as the ship loomed tall before them, its sails like clouds. They stopped, uncertain, but the sailors beckoned.

When the canoe drew near, the young men called out in their language. To their shock, one white sailor replied in the same tongue. “I have come,” he declared, “to buy the tusks of the beast that roams your forests with great feet, tusks, and ears. He is called Njaku.”

The men nodded eagerly. “Yes, that is good,” they replied. Before they left, the sailor handed them four bunches of tobacco, four bales of bright printed cloth, four caps, and other goods.

Back on shore, they spread the news: the white men wanted Njaku’s tusks. Even more, they brought weapons, guns, powder, and bullets, to help kill him and his kind.

The very next morning, armed with these new tools, the townspeople entered the forest. For two days they fought the elephants, killing many, and loading the tusks onto the ship. When the ship was full, it sailed away.

And so it has continued to this very day: the ivory trade, born from Njaku’s anger, Bokume’s gift of wood, and Uhadwe’s path across the sea.

Moral Lesson

This tale reveals how choices shape destiny. Njaku’s anger made him feared and hunted, his ivory exploited by outsiders. Bokume’s obedience brought him transformation into a tree of great value, offering shelter and livelihood. Uhadwe’s wisdom connected the land to the sea, but also opened the path for trade that carried both gifts and sorrow. The story reminds us that pride and rage often bring destruction, while humility and balance create legacies that endure.

Knowledge Check

Who were the three brothers in the tale?

Uhadwe, Bokume, and Njaku, sons of a mortal mother under Njambi the Creator.

What did Bokume transform into?

Bokume became the mahogany tree, also called okume.

Why did Njaku become the first elephant?

He defied Uhadwe’s command, sought to live among townspeople, and transformed in anger.

What lasting marks did Uhadwe leave at Corisco Bay?

Bush-rope, mangrove forests, and his footprints with his dog pressed into the rocks.

What did the white sailors seek from the villagers?

They came to trade for elephant tusks (ivory).

What cultural practice does this tale explain?

The origin of the ivory trade in Equatorial Guinea.

Source: Equatorial Guinean folktale