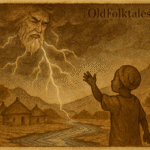

Come close, children of the flowing waters, gather as the evening mist rises from the valleys of our beloved Maluti. Sit still as the pools that mirror the sky, for tonight I shall pour into your hearts a story that flows from the deepest springs of our people’s wisdom. This is the tale of Mohokare, the great river that forgot how to sing.

Listen well, for in the time when the world was younger and the mountains wore crowns of eternal snow, there flowed through our land a river so mighty that its voice could be heard singing from the peaks to the plains. The people called her Mohokare, which means “the bringer of life,” for her crystal waters fed their crops, filled their calabashes, and carried their prayers to the ancestors dwelling in the distant sea.

Metsi a phela, batho ba phela Water lives, people live, as our grandmothers say, and so it was that the villages along Mohokare’s banks grew fat and prosperous like cattle in green pastures.

But this river, children, was no ordinary stream. The ancestors had blessed her with the spirit of Mamlambo, the great water serpent, whose watchful eyes could see into the hearts of all who came to drink from her waters. Mohokare knew the thoughts of every person who knelt upon her banks, felt every emotion that touched her flowing currents, and remembered every promise spoken over her sacred pools.

In those days, three villages shared the bounty of Mohokare’s gifts. There was Mahlabeng, the village of red stones, where the potters made vessels so fine they could hold moonlight without breaking. There was Phahameng, the village of high places, where the herders grazed cattle whose milk was sweet as morning honey. And there was Thabeng, the village of the mountain, where the farmers grew sorghum and maize that stood tall as young trees.

For many seasons, these villages lived like fingers on the same hand, each different but working together for the good of all. When Mahlabeng’s potters needed clay, Phahameng’s herders would guide them to the best deposits. When Phahameng’s cattle needed grazing, Thabeng’s farmers would share their fields after harvest. When Thabeng needed vessels for their grain, Mahlabeng’s potters would craft them with songs of blessing.

Motho o motho ka batho A person is a person through other people, and so these three villages understood the ancient wisdom that makes communities strong.

But as the seasons turned like the great wheel of stars, prosperity began to plant seeds of selfishness in some hearts. The people of each village started to whisper among themselves like wind through dry grass.

“Why should we share our finest clay with others?” murmured the potters of Mahlabeng. “Let them find their own.”

“Why should our sweet milk feed children who are not our own?” grumbled the herders of Phahameng. “Our cattle give only so much.”

“Why should our golden grain fill the stomachs of strangers?” complained the farmers of Thabeng. “We have worked hardest for this harvest.”

Lerato le fela, metsi a oma When love ends, water dries, whispered the ancestors, but the people had stopped listening to the old voices.

Soon the three villages began to build walls between themselves. They marked boundaries with stones, set guards at the crossings, and spoke to each other only in anger and suspicion. The children who had once played together across village lines were forbidden to meet. The young people who had found love in neighboring villages were forced to forget their sweethearts. The elders who had shared wisdom for generations turned their backs on old friends.

And Mohokare, the sacred river, felt every harsh word like a stone thrown into her peaceful waters. She tasted the bitterness of broken friendships, the salt of unshed tears, the poison of pride that seeped from the villages into her once pure streams.

Noka e a utloa, noka e a bona The river hears, the river sees, for water remembers everything that touches it.

One morning, when the first light painted the mountain peaks with golden fire, the most terrible thing happened. The people of Mahlabeng woke to find their portion of the river bed dry as old bones. The people of Phahameng discovered their waters had become bitter as wormwood. The people of Thabeng saw their section of the mighty Mohokare flowing backward, defying every law of nature and sense.

Mohokare had stopped flowing forward. The great river, wounded by the hatred between the villages, had withdrawn her blessing. Her waters pooled in stagnant lakes, or disappeared entirely into the earth, or flowed in impossible directions that made no sense to human understanding.

Ha metsi a ema, bophelo bo a fela When water stops, life ends, and so it began to be.

The crops withered like old women’s hands. The cattle lowed pitifully, their udders dry. The clay beds cracked like broken hearts. Children cried for water, mothers searched desperately for any drop to wet their lips, and the elders shook their heads, remembering warnings their own grandparents had given about the price of division.

But pride is a stubborn weed that grows deep roots. Instead of admitting their fault, each village blamed the others for the river’s curse.

“The potters of Mahlabeng must have angered the water spirits with their greed!” shouted the people of Phahameng.

“The herders have polluted the sacred pools with their cattle!” cried the people of Thabeng.

“The farmers have taken too much water for their fields!” accused the people of Mahlabeng.

And so the arguing grew louder while the drought grew worse, until even the mountain springs began to fail.

It was old Mmamotse, the oldest woman in all three villages, who finally spoke the truth that everyone had forgotten. She was so ancient that her hair was white as cloud and her voice thin as mountain wind, but her words carried the weight of seven generations of wisdom.

“Children,” she called, her voice somehow reaching every ear in every village despite its frailness, “do you not see? The river has not left us. We have left each other. Mohokare flows with the love between neighbors, not with the rain from the sky. She is dry because our hearts have become dry. She is bitter because our words have become bitter. She flows backward because we have turned our backs on the path our ancestors walked.”

Noka e phalla moo batho ba dumalanang The river flows where people agree, and these words struck the people’s hearts like lightning strikes the high peaks.

That very evening, as the sun set red behind the mountains, representatives from all three villages met at the dried riverbed where their boundaries came together. There, on the cracked earth that had once known the kiss of flowing water, they began to speak truths that had been locked in their hearts.

“We were wrong to hoard our clay,” admitted the potters of Mahlabeng. “The earth gives her gifts to all people, not just to us.”

“We were selfish with our milk,” confessed the herders of Phahameng. “A cow’s blessing should nourish all children, not just our own.”

“We were greedy with our grain,” acknowledged the farmers of Thabeng. “The harvest belongs to those who hunger, wherever they may live.”

As each truth was spoken, as each apology was offered, as each hand reached out to clasp another in forgiveness, something wonderful began to happen. Deep beneath the dry riverbed, they heard the sound of water moving, like the whisper of returning life.

By morning, Mohokare was flowing again. Her waters ran clear as mountain crystal, sweet as the first rain after drought, singing the ancient songs of joy that had been silent for too many moons. The three villages tore down their walls, opened their borders, and celebrated with a feast that lasted for seven days and seven nights.

From that day forward, the people remembered the lesson of the river that refused to flow. They built their settlements not as separate kingdoms but as parts of one great community. They shared their gifts freely, settled their disputes with wisdom rather than anger, and taught their children that the strength of water comes not from any single drop, but from all drops flowing together toward the same destination.

And Mohokare flowed on, carrying their prayers to the ancestors, their hopes to the sea, and their love to future generations yet unborn.

The Wisdom of the Ancestors

Thus do the waters teach us, children of the mountains, that life flows not in isolation but in unity. Like the many streams that join to form the mighty river, like the many stones that build the strong foundation, we are strongest when we stand together and weakest when we stand apart.

The river that refused to flow shows us that our communities are like living waters they thrive when love and cooperation flow freely between us, but they stagnate and die when we build barriers of selfishness and pride. The earth’s gifts are meant to be shared, for no village, no family, no person can thrive alone in this world.

When we look upon our neighbors with suspicion instead of friendship, when we hoard our blessings instead of sharing them, when we build walls instead of bridges, we do not just harm others we harm ourselves. For we are all connected like tributaries to the same great river, and what affects one affects all.

Let us therefore be like the wise waters that know no boundaries, that flow freely between all lands, that give life wherever they are needed. Let us remember that true strength comes not from what we can keep for ourselves, but from what we can give to others. And let us never forget that the river of life flows strongest when all its people flow together in harmony, respect, and love.

Ubuntu We are, because we are together, as the great truth echoes across all the lands of Africa.

Knowledge Check

What caused the sacred river Mohokare to stop flowing in this Sotho folktale?

Mohokare stopped flowing because the three villages Mahlabeng, Phahameng, and Thabeng abandoned their cooperative relationships and became selfish and suspicious of each other. The river, blessed with the spirit of Mamlambo the water serpent, was hurt by the hatred and division between communities that had once lived in harmony.

How do the three villages represent different aspects of traditional African communities?

The three villages represent complementary community roles: Mahlabeng (pottery and crafts), Phahameng (livestock and herding), and Thabeng (agriculture and farming). Their interdependence reflects traditional African economic systems where different communities specialized in various skills but shared resources and supported each other.

What role does the elderly character Mmamotse play in resolving the water crisis?

Mmamotse represents ancestral wisdom and serves as the voice of truth that cuts through the villages’ pride and blame. Her age and experience give her the authority to speak uncomfortable truths, and she helps the people understand that their spiritual and physical drought stems from their broken relationships, not natural causes.

How does this African water folklore teach environmental stewardship to children?

The story teaches that environmental health is connected to community health and human behavior. It shows how natural resources like rivers respond to human actions, emphasizing that environmental problems often have social causes and require community cooperation to solve, making it relevant for modern environmental education.

What traditional Sotho proverbs enhance the moral lessons in “The River That Refused to Flow”?

The story incorporates proverbs like “Metsi a phela, batho ba phela” (Water lives, people live), “Motho o motho ka batho” (A person is a person through other people), and “Noka e phalla moo batho ba dumalanang” (The river flows where people agree), which reinforce themes of interdependence and community harmony.

How can educators use this Sotho folktale to teach conflict resolution and community building?

Teachers can use this story to discuss how communities can resolve conflicts through honest communication, mutual understanding, and shared responsibility. The tale demonstrates that lasting solutions require all parties to acknowledge their mistakes, make amends, and commit to cooperation rather than just addressing surface problems.