In a land where the sun blazed hot and unforgiving, there lived a humble family, a father, a mother, and their two children. The son, Koane, was responsible for herding the family’s cattle to the sweetest grasses each morning when the air was still cool. The daughter, Thakane, kept their home, preparing meals and tending to their needs. Their parents worked tirelessly in the fields from dawn until dusk, resting only when the midday heat became unbearable beneath the shade of ancient trees.

At the center of their small garden stood Koumongoe, a sacred tree that produced the finest milk in all the world. But this tree was forbidden to the children, it belonged to their parents alone, a source of sustenance and survival that must never be touched by young hands.

One fateful morning, Koane awoke later than usual. His parents had already departed for the fields, leaving only Thakane at home, kneading dough for the evening’s bread. Koane stretched lazily and called to his sister with a demanding voice.

Don’t miss out: Read more Southern African folktales

“Thakane, I’m thirsty. Bring me milk from Koumongoe.”

Thakane’s hands froze in the dough. “You know we’re forbidden to touch that tree! Father would know immediately. Please, Koane, don’t ask me to do this.”

But Koane’s face darkened with stubborn anger. “If you won’t give me the milk, then I won’t take the cattle out to graze. They can stay locked in the hut all day and starve. See if I care.”

He turned away and sulked in the corner, arms crossed, refusing to move. Thakane felt her heart sink with dread. If the cattle weren’t fed, they would weaken and perhaps die and she would be blamed. Yet if she disobeyed her parents and touched the sacred tree, punishment would surely follow. Trapped between two terrible choices, she finally made her decision.

Taking up an axe and a small earthen bowl, Thakane approached Koumongoe with trembling hands. She cut the tiniest hole she could manage in its bark. Milk gushed forth, filling the bowl quickly. She brought it to her brother, hoping this would satisfy him.

Koane looked at the bowl with contempt. “What’s this? There’s barely enough to drown a fly! Go back and bring me three times as much.”

Terror gripped Thakane’s chest, but she returned to the tree. This time, she struck it harder with the axe. The result was catastrophic milk exploded from Koumongoe like a raging river, flooding the hut and pouring out the doorway. It streamed down the hillside toward the fields where their parents labored.

“Koane! Help me stop it!” Thakane screamed, but neither she nor her brother could plug the gaping wound in the tree. The white torrent continued its relentless flow downward.

In the fields below, their father spotted the strange white river cascading down the hill. Recognition struck him like lightning. “Wife! Look, Koumongoe is flowing down to us! The children have done something terrible. We must go home at once!”

They dropped their hoes and ran. When they reached the river of milk, they knelt on the grass, cupped their hands together, and drank deeply. The moment the sacred milk touched their lips, Koumongoe reversed its course, flowing backward up the hill and returning to its place in the garden.

When the parents reached home, breathless and furious, they found their children standing amid the puddles of milk. “Thakane,” her father said, his voice cold as stone, “what have you done? Why did Koumongoe leave its place and come to us in the fields?”

Thakane’s voice trembled as she explained. “It was Koane’s fault, Father. He refused to take the cattle unless I gave him milk from the sacred tree. I didn’t know what else to do.”

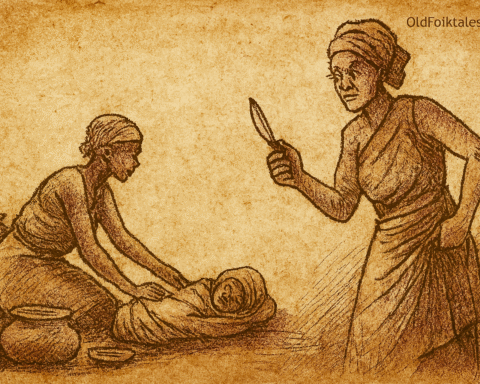

Her father said nothing. His silence was more terrifying than any shout. He left the hut and returned with two sheepskins, which he dyed deep red. He summoned a blacksmith to forge iron rings, then fastened the rings around Thakane’s arms, legs, and neck. The heavy sheepskins were bound to her body, front and back, marking her for a grim fate.

“I am taking Thakane away,” he announced to his servants.

“Away? But why would you get rid of your only daughter?”

“Because she has violated what is sacred. She has touched the tree that belongs only to her mother and me. She must face the consequences.”

He turned his back on the household and commanded Thakane to follow. They walked down the dusty road leading to the dwelling of a fearsome ogre, a creature known for devouring human flesh.

As they passed through fields of ripening corn, a rabbit suddenly sprang up before them, standing on its hind legs. It sang in a clear, haunting voice:

Why do you give to the ogre

Your child, so fair, so fair?

“Ask her yourself,” the father replied coldly. “She’s old enough to answer.”

Then Thakane sang, her voice breaking with sorrow:

I gave Koumongoe to Koane,

Koumongoe to the keeper of beasts;

For without Koumongoe they could not go to the meadows:

Without Koumongoe they would starve in the hut;

That was why I gave him the Koumongoe of my father.

The rabbit’s eyes blazed with righteous anger. “Wretched man! It is you the ogre should devour, not your beautiful, innocent daughter!”

But the father ignored the rabbit’s words and walked faster, Thakane struggling to keep pace under the weight of the skins and iron rings. Soon they encountered a majestic herd of elands, who stopped and sang the same mournful question. Thakane gave the same answer, and the elands cried out the same condemnation of her father.

As darkness fell, they stopped to rest. Thakane collapsed onto the ground, exhausted and terrified, yet sleep claimed her quickly. At dawn, her father woke her roughly, and they continued their terrible journey. They passed gazelles grazing in the morning light, and once again the animals sang their question, received Thakane’s answer, and condemned her father for his cruelty.

Finally, they arrived at the ogre’s village. But when they entered the main hut, they found not the ogre but his son, Masilo, a kind and courteous young man, nothing like his monstrous father. Masilo ordered fine skins to be laid out for Thakane to sit upon, while her father was told to sit on the bare ground.

When Masilo saw Thakane’s face, he was struck by her beauty and gentleness. He asked why she was being brought to his father, and she sang her sorrowful explanation once more. Moved by compassion, Masilo commanded that Thakane be taken to his mother’s care, while her father was led to the ogre.

The ogre took one look at the man and ordered him thrown into the great cooking pot that always bubbled over the fire. Within minutes, the father who had condemned his innocent daughter was himself consumed.

Masilo, who had spent his whole life hating women and refusing every bride his parents suggested, found himself inexplicably drawn to Thakane. For the first time, his heart opened to love. His parents, desperate for him to marry, welcomed Thakane gladly as their daughter-in-law, even though she brought no dowry.

In time, Thakane gave birth to a baby girl. She gazed at her daughter with overwhelming love, thinking her the most beautiful child ever born. But when Masilo’s mother saw the infant, she began to weep and wring her hands.

“O miserable mother! Miserable child! Why were you not born a boy?”

Thakane clutched her baby close, alarmed. “What do you mean? Why do you mourn?”

The old woman explained with tears streaming down her face. “In this country, it is the custom that all baby girls must be given to the ogre to eat.”

Horror flooded through Thakane. “That is not the custom in my country! There, when children die, they are buried in the earth with honor. No one will take my baby from me no one!”

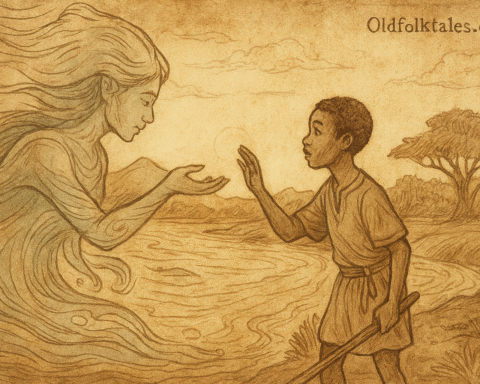

That night, when the household slept, Thakane rose silently. She tied her baby to her back and crept out into the darkness, following the path to the river. Where the water spread into a wide lake surrounded by tall willows, she sat down on a stone and wept, trying desperately to think of how to save her child.

A rustling sound made her look up. An old woman emerged from between the willow trees, her face kind and weathered with age.

“Why do you weep, my dear?” the old woman asked gently.

“I weep for my daughter,” Thakane sobbed. “I cannot hide her forever, and when the ogre discovers her, he will devour her. I would rather drown her in this lake than let that monster have her.”

The old woman nodded slowly. “Your words are true. Give me your child, and I will care for her beneath the waters. Come to this place whenever you can, and I will bring her to you.”

Thakane dried her tears and placed her precious baby in the old woman’s arms. When she returned home, she told Masilo that she had thrown the child into the river. He had seen her go in that direction and believed her words.

On the appointed days, Thakane would slip away to the lake and hide among the willows. She would sing softly:

Bring to me Dilah,

Dilah the rejected one,

Dilah, whom her father Masilo cast out!

Each time, the old woman would emerge from the water with little Dilah. The child grew with magical speed in the underwater realm, becoming stronger and more beautiful with each visit. Thakane cherished these stolen moments with her daughter, playing and laughing before she had to return to the village.

Time passed swiftly beneath the lake, and soon Dilah transformed from infant to young woman. One day, as Thakane sat talking with her grown daughter by the water’s edge, a man came to cut willow branches for basket-weaving. He stopped in astonishment when he saw the girl, for her face was the mirror image of Masilo’s.

He rushed back to the village and found Masilo. “I have seen your wife by the river with a young woman who must be your daughter she looks exactly like you! We have all been deceived. The child is not dead.”

Masilo’s heart leaped with joy, though he pretended to be shocked by his wife’s deception. “What should I do?” he asked.

“Hide among the bushes the next time Thakane goes to bathe. See for yourself if I speak the truth.”

Several days passed before Thakane announced she was going to the river. “Go ahead,” Masilo said casually. But he ran by a different path and concealed himself in the dense bushes before she arrived.

Thakane stood on the bank and sang her summoning song. The old woman rose from the lake, leading by the hand a tall, graceful young woman. Masilo’s breath caught in his throat this was indeed his daughter, alive and radiant, not lying dead at the bottom of the lake. Tears of joy streamed down his face.

But the old woman sensed something amiss. “I feel as though we are being watched. I will not leave Dilah with you today.” She pulled the girl back beneath the surface, and they vanished into the depths.

Masilo returned to the village before Thakane and sat in a corner, weeping. His mother found him there and asked, “Why do you cry so bitterly, my son?”

“My head aches terribly,” he lied, and she left him alone.

That evening, he confronted Thakane. “I have seen our daughter alive in the place where you told me you drowned her. She lives at the bottom of the lake and has grown into a beautiful young woman.”

Thakane’s face remained still. “I don’t know what you’re talking about. I buried my child in the sand on the beach.”

Masilo begged her to bring their daughter back, but Thakane refused. “If I return her to you, you will only follow the laws of your people and take her to your father the ogre, and she will be eaten.”

“I promise I will never let my father see her,” Masilo pleaded. “She is a woman now no one can harm her. Please, Thakane, give me back my daughter.”

Finally, Thakane’s resolve weakened. She went to the lake and summoned the old woman. “Masilo has seen Dilah, and he begs me to return her to him. What should I do?”

The old woman’s eyes gleamed. “If he wants his daughter back, he must pay me one thousand head of cattle in exchange for raising her.”

When Thakane delivered this message, Masilo exclaimed, “I would gladly give her two thousand for saving my daughter!” He sent messengers throughout all the neighboring villages, commanding his people to send every cow and bull they owned. When the cattle were assembled, a vast, lowing herd that stretched across the plain, Masilo chose the finest thousand and drove them to the river.

A great crowd followed, eager to witness what would happen. Thakane stepped forward before the herd and sang:

Bring to me Dilah,

Dilah the rejected one,

Dilah, whom her father Masilo cast out!

Dilah rose from the waters, her hands outstretched toward her parents, her face shining with happiness. As she stepped onto the shore, the thousand cattle walked into the lake and disappeared beneath its surface, driven by the old woman to the great city filled with people that lies forever at the bottom of the world.

Moral Lesson

This folktale teaches us profound truths about sacrifice, injustice, and redemption. Thakane’s punishment for a selfless act reveals the cruelty of rigid rules applied without wisdom or mercy. Her father’s harsh judgment ultimately destroys him, while Thakane’s compassionate choice made under impossible circumstances demonstrates true parental love. The story also speaks to the value of female children in societies where they were considered disposable, showing that daughters possess inherent worth regardless of cultural customs. Finally, it illustrates that what is hidden and protected can grow into something beautiful and valuable, and that true justice, though delayed, will eventually emerge from the depths.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who is Thakane in the African folktale of Koumongoe?

A: Thakane is the daughter who disobeys her father by giving sacred milk from the tree Koumongoe to her brother Koane. Despite acting out of compassion to prevent the cattle from starving, she is punished by being taken to an ogre, though she ultimately finds redemption.

Q2: What does the sacred tree Koumongoe symbolize in the story?

A: Koumongoe represents forbidden sustenance and the boundaries between sacred and profane. It symbolizes parental authority and the harsh consequences of breaking taboos, even when done for selfless reasons. The milk flowing down the hill serves as a metaphor for how violations of sacred rules cannot be hidden.

Q3: Why does Thakane hide her daughter Dilah underwater?

A: Thakane hides Dilah with an old woman beneath the lake to save her from being eaten by the ogre, as it was the custom in her husband’s country that all baby girls be given to the ogre. She chooses this desperate measure to protect her daughter from a cruel tradition.

Q4: What is the moral lesson of The Sacred Milk of Koumongoe?

A: The tale teaches that rigid adherence to rules without compassion leads to injustice, and that those who show mercy deserve redemption. It also emphasizes the inherent value of daughters and challenges harmful cultural practices, while illustrating that protective love can preserve what society deems worthless until justice prevails.

Q5: What cultural origin does the Koumongoe folktale come from?

A: This folktale originates from African oral tradition and appears in Andrew Lang’s fairy book collections, representing the rich storytelling heritage of African cultures. It reflects themes common in African folklore about sacred trees, shape-shifting beings, and the testing of parental love.

Q6: How does Masilo differ from his ogre father in the story?

A: Unlike his monstrous father who devours humans, Masilo is kind, courteous, and just. He shows compassion to Thakane, falls in love with her despite previously hating women, and ultimately works to save their daughter rather than following the cruel custom of sacrificing baby girls to the ogre.

Source: African folktale, collected in Andrew Lang’s Fairy Books