Come close, children of the burning sand, come close,

Listen to the tale of water and wisdom,

Listen to the story of Khaa the Great Serpent,

Who guarded the last waterhole in the time of great thirst…

Long, long ago, when the Kalahari stretched endless as the star-scattered sky, there came a drought so fierce that the very stones cracked like broken ostrich eggs. The sun burned merciless overhead, turning the red sand white-hot beneath bare feet. One by one, the waterholes dried to cracked clay, the seasonal pans became dust bowls, and the great river shrank to a memory whispered by the wind.

Hot sand burns, hot wind blows,

Where the water went, nobody knows,

Dry earth cracks, dry throat calls,

Death walks tall when the water falls…

In all the vastness of the desert, only one waterhole remained a deep, sacred pool hidden in a rocky kloof where the red cliffs cast shadows like prayers. This was Gam gam, the Singing Waters, where the ancestors had drunk since the first people walked the earth. Its waters bubbled up from the deep heart of the world, sweet and clear as liquid diamonds.

But Gam gam was guarded by Khaa, a serpent so ancient and vast that the elders said he had been coiled around the waterhole since the world was young. His scales shimmered like heated metal, copper and bronze and gold, each one as large as a man’s hand. His eyes were like pools of liquid amber that held the wisdom of countless seasons.

Khaa the Ancient, Khaa the Wise,

Golden scales and amber eyes,

Coiled around the sacred spring,

Guardian of the water’s ring…

The people grew desperate as the drought stretched on. Children cried with cracked lips, the elderly grew weak as dried grass, and even the strongest hunters moved slowly in the terrible heat. The clan leaders gathered in council, their voices hoarse as wind through thornbush.

“We must have water from Gam gam,” said Toma, the headman, his face gaunt with worry. “Our people are dying of thirst.”

“But Khaa guards it fiercely,” whispered old Nai, her voice like rustling leaves. “He allows no one to drink without permission.”

“Then we shall take what we need by force,” declared young Gaqo, shaking his spear. “What is one snake against the needs of our people?”

Pride speaks loud when water’s low,

Young men think that strength can show,

But desert wisdom knows the way

Respect must come before you pray…

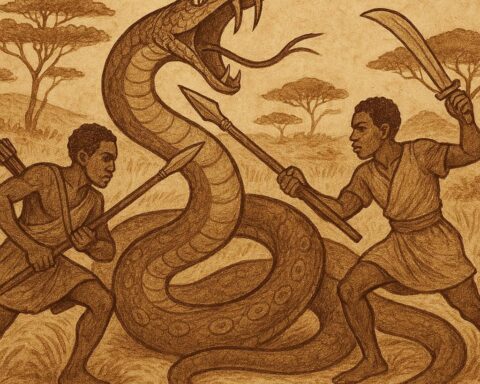

Against the counsel of the elders, Gaqo and his hunters marched to Gam gam in the burning heat of midday. They found the great serpent coiled around the waterhole, his massive head resting on the rocks, eyes closed as if sleeping. The water sparkled like stars fallen to earth, so clear and beautiful that the men’s throats ached with longing.

“Move aside, snake!” shouted Gaqo, raising his spear. “We will have water, and you cannot stop us all!”

Khaa opened one great eye, the amber depths reflecting not anger but profound sadness. “Young hunter,” he said, his voice like distant thunder, “I do not guard this water to deny it to those who need it. I guard it to ensure it lasts for all who come with proper respect.”

Water calls and thirsts demands,

But wisdom flows from patient hands,

The serpent speaks with voice of old,

His words more precious than fine gold…

But Gaqo’s desperation had made him deaf to wisdom. He hurled his spear at the great serpent, and his hunters followed with their own weapons. The spears bounced harmlessly off Khaa’s scales, ringing like metal on stone.

The ancient serpent rose up, his great coils shifting with the sound of boulders rolling. He was enormous thick as a baobab tree, long as a seasonal river. Yet he did not strike the foolish hunters. Instead, he simply curved his massive body more tightly around the waterhole, blocking all access to its life-giving depths.

“Since you come with violence instead of respect,” Khaa said sadly, “the water is closed to you until you learn the proper way.”

Spears like straws against the great,

Pride has sealed the hunters’ fate,

Khaa coils tight around the spring,

Water hides from angry sting…

The hunters returned to their people empty-handed, their shame burning hotter than the desert sun. The clan grew weaker, and still the drought stretched on. Children no longer played, and the old ones began to speak of the final journey to the ancestor spirits.

It was then that little Xabbu, barely old enough to hold a digging stick, approached her grandmother Nai. “Grandmother,” she whispered, “why did the snake close the water to us?”

Old Nai’s eyes, clouded with age but bright with wisdom, focused on her granddaughter. “Because, little one, we forgot the old ways. We forgot that we are not masters of the water we are its children, and it is our mother.”

Child asks with heart so pure,

Grandmother’s wisdom is the cure,

Old ways call from ancient time,

Respect the water, heal the crime…

“What are the old ways, Grandmother?”

Nai smiled, her cracked lips barely moving. “The old ways say we must approach Khaa as children approach their parents with humility, with gratitude, with recognition that we are small and the world is vast.”

The next dawn, as the sun painted the desert cliffs the color of fresh blood, little Xabbu walked alone to Gam gam. She carried no spear, no fighting stick, only a small ostrich eggshell to carry water back to her people.

Small feet on the burning sand,

Empty shell in tiny hand,

Child walks where warriors failed,

Where pride was broken, love prevailed…

She found Khaa coiled around the waterhole as before, but now his great head was raised, watching her approach. Xabbu stopped at a respectful distance and sat down in the sand, folding her small legs beneath her.

“Great Khaa,” she said, her child’s voice clear in the desert silence, “I come not to demand, but to ask. My people are dying, and we need your permission to drink from the sacred waters. We know we acted wrongly. We ask for your forgiveness and your blessing.”

The ancient serpent studied the small girl for a long moment. In her eyes he saw no arrogance, no demand, no assumption that the water belonged to her people by right. He saw only humility, need, and respect.

Child speaks what warriors could not say,

Humility lights the way,

In small voice, the great truth rings

Respect is worth more than kings…

“Little daughter,” !Khaa said gently, “you understand what your elders forgot. The water belongs to no one and everyone. It flows for all who approach it with gratitude, who take only what they need, who remember that they are part of the great web of life, not its masters.”

Slowly, the great serpent unwound himself from around the waterhole, his scales catching the morning light like scattered coins. “Drink,” he said. “Fill your shell. Return to your people and teach them what you have learned.”

Xabbu filled her ostrich eggshell and bowed deeply to the serpent guardian. “Thank you, Great Father,” she whispered.

Water flows like liquid light,

Child has made the desert bright,

Humility opens every door,

That pride had closed and barred before…

She returned to her people and shared not only the precious water but the greater gift of wisdom. From that day forward, the San approached Gam gam with proper ceremony bringing offerings of gratitude, speaking words of respect, taking only what they needed and always asking permission.

Khaa the Great Serpent remained the guardian of the sacred waters, but now he welcomed all who came with humble hearts. The waterhole never ran dry, even in the worst droughts, for those who approached it with respect found that Khaa’s protection extended not just to the water itself, but to all who honored the ancient ways.

Now the people know the way,

How to ask and how to pray,

Water flows for those who see

We are part of harmony…

And to this day, when the San people find a waterhole in the deep desert, they approach it with the same reverence little Xabbu showed to Khaa, knowing that water is not something to be taken by force, but a sacred gift to be received with gratitude and protected with wisdom.

This is how the story goes,

How the desert wisdom flows,

Humble hearts and respectful hands,

Find water in the thirsty lands…

The Sacred Teaching

The great serpent Khaa teaches us that true power lies not in taking what we want by force, but in understanding our place within the greater web of existence. In our modern world, we often approach nature as conquerors rather than children, demanding rather than requesting, taking rather than receiving. The waterhole represents all of nature’s gifts clean air, fertile soil, flowing rivers, abundant harvests that sustain our lives. Like the ancient San, we must learn that these are not resources to be exploited but sacred trusts to be honored. Humility before nature means recognizing that we are not separate from the natural world but part of it, dependent upon its generosity and subject to its laws. When we approach the earth with gratitude instead of greed, with respect instead of arrogance, with the understanding that we are temporary visitors rather than permanent owners, we find that nature responds with abundance. The child Xabbu succeeded where warriors failed because she understood what modern humanity often forgets that the greatest strength lies in acknowledging our smallness, the greatest wisdom in admitting our dependence, and the greatest power in approaching the sacred sources of life with the humble heart of a child asking a beloved parent for help.

Knowledge Check: San Water Stories and Desert Survival

Q1: What significance do waterhole guardian stories like “The Snake That Guarded the Waterhole” hold in San desert culture? A1: San waterhole guardian stories teach crucial desert survival wisdom—that water sources are sacred and must be approached with respect, ceremony, and gratitude. These folktales preserve ancient protocols for finding and sharing scarce water resources while emphasizing that survival depends on maintaining proper spiritual relationships with natural forces.

Q2: How do traditional San folktales about serpent guardians reflect actual desert ecology and water conservation? A2: San serpent guardian stories encode practical knowledge about desert water sources, teaching that waterholes require protection from overuse and contamination. The serpent represents natural balance—these stories teach sustainable water use, proper approaching protocols, and the understanding that water sources must be preserved for long-term community survival.

Q3: What role does humility play in San folktales about human-nature relationships like “The Snake That Guarded the Waterhole”? A3: Humility is central to San survival philosophy because desert life requires recognizing human dependence on natural forces beyond human control. Folktales teaching humility before nature help ensure that people approach scarce resources like water with respect rather than arrogance, leading to sustainable practices and community survival.

Q4: How do San desert folktales use child characters to convey wisdom about environmental respect? A4: San stories often feature children succeeding where adults fail because children represent purity of intention, natural humility, and openness to learning. Child characters in environmental folktales teach that approaching nature with innocent respect and genuine need, rather than adult pride and demands, leads to cooperation and abundance.

Q5: What traditional San water ceremonies and protocols are reflected in snake guardian folktales? A5: San snake guardian stories preserve ancient water ceremony protocols including approaching water sources with offerings, speaking respectful words, taking only what’s needed, and asking permission from guardian spirits. These folktales maintain traditional knowledge about proper behavior around sacred water sources essential for desert survival.

Q6: How do San folktales about water guardians teach sustainable resource management in harsh environments? A6: San water guardian stories teach that sustainable resource use requires recognizing limits, showing respect for natural systems, and understanding that humans are part of larger ecological relationships. These folktales encode practical wisdom about managing scarce desert resources through spiritual respect and community cooperation rather than individual exploitation.