In a prosperous town where justice was dispensed and laws upheld, there lived a judge of great renown. He had wealth, respect, and influence, yet his heart remained heavy, for he and his wife had no children to carry on their name. One afternoon, as he stood before his house, lost in melancholy thoughts, an elderly stranger approached him.

“What troubles you, sir?” the old man asked gently. “Your face is clouded with sorrow.”

“Leave me be, good man,” the judge replied wearily.

But the stranger persisted. “Tell me what burdens your heart.”

Fascinated by this tale? Discover more North African folktales

The judge sighed deeply. “I have achieved success in my profession and earned the respect of this town, but what does it matter? I have no children, no legacy, no future beyond myself.”

The old man’s eyes twinkled with mysterious knowledge. “Here,” he said, producing twelve perfect apples from his cloak. “If your wife eats these, she will bear you twelve sons.”

The judge’s heart leaped with joy as he accepted the precious gift. He rushed home to his wife, crying out, “Eat these apples at once! They will give us twelve sons!”

His wife sat down eagerly and consumed the first apple, then the second, third, and so on. She had eaten eleven whole apples and was halfway through the twelfth when her sister arrived for a visit. In a gesture of sisterly affection, she gave her the remaining half.

In due time, eleven strong, handsome boys were born to the judge and his wife. But when the twelfth child arrived, there was only half of him, one arm, one leg, half a body, and half a face. Yet despite his unusual form, this Halfman possessed a sharp mind and extraordinary courage that would prove greater than any physical completeness.

The years passed, and the brothers grew into men. One day they approached their father, declaring it was time they took wives. “I have a brother who lives in the East,” the judge told them, “and he has twelve daughters. Go and marry them.”

The twelve sons saddled their horses and rode eastward for twelve days until they encountered an old woman on the road. “Greetings, young men!” she called warmly. “We have waited so long for you, your uncle and I. The girls have become women, and though many have sought them in marriage, I knew you would come eventually. Follow me to my house.”

The brothers followed gladly, and at the house a man stood waiting, welcoming them with abundant food and drink. But that night, when darkness fell and everyone slept, Halfman crept silently to his brothers’ bedsides.

“Listen!” he whispered urgently. “This man is no uncle of ours, he is an ogre!”

“Nonsense!” his brothers scoffed. “Of course he’s our uncle.”

“You will see tonight,” Halfman warned grimly. Instead of sleeping, he hid himself in the shadows and watched.

Soon the ogre’s wife entered the room on silent feet. She spread a red cloth over the brothers, then covered her own daughters with a white cloth before returning to bed. When her snores echoed through the house, Halfman moved swiftly. He exchanged the cloths, placing the red one over the ogre’s daughters and the white one over his brothers. Then he switched their scarlet caps with the veils worn by the girls. His work complete, he concealed himself in the curtain folds—there was only half of him, after all.

Heavy footsteps approached. The ogress returned, her tiny lantern casting barely enough light to see. She bent down, examining the red cloth and feeling the caps on the heads beneath it. Satisfied these were the brothers, she began killing them one by one.

“Get up!” Halfman hissed to his brothers. “Run for your lives, the ogress is murdering her own daughters!”

The brothers fled into the night. Behind them, the last daughter awoke, screaming, “Mother, what have you done? You’ve killed my sisters!”

“Halfman has outwitted me!” the ogress wailed, but the brothers were already far away.

They rode until they reached their true uncle’s town. When they found him, he asked, “Why have you taken so long?”

“We nearly didn’t arrive at all!” they explained, recounting their narrow escape. “If not for Halfman’s cleverness, we would all be dead. Now, uncle, give us your daughters as wives.”

“Take them gladly,” their uncle replied. “The eldest for the eldest, the second for the second, down to the youngest.”

But Halfman’s bride was the most beautiful of all, and jealousy burned in his brothers’ hearts. “Why should he who is only half a man receive the best?” they muttered darkly. “Let us kill him and give his wife to our eldest brother.”

After riding some distance with their brides, they came to a brook. “Who will fetch water?” one brother asked.

“Halfman is the youngest, he must go,” declared the eldest.

Halfman descended into the stream and filled a waterskin. His brothers pulled it up by rope and drank deeply. When they finished, Halfman called from the middle of the current, “Throw me the rope! I cannot climb out alone.”

They lowered the rope, and Halfman began climbing the steep bank. But halfway up, they cut the rope, sending him plummeting back into the water. Then they rode away with his bride, leaving him to drown.

Halfman sank beneath the surface, but before he struck bottom, a fish appeared. “Fear nothing, Halfman,” it said. “I will help you.” The fish guided him to shallow water where he could climb out.

“Do you understand what your brothers whom you saved from death have done to you?” the fish asked.

“Yes, but what can I do?”

“Take one of my scales. When you find yourself in danger, throw it into fire, and I will appear.”

Halfman thanked the fish and wandered through the unfamiliar countryside until suddenly the ogress materialized before him. “Ah, Halfman! At last I have you! You killed my daughters and helped your brothers escape. What shall I do with you?”

“Whatever you wish,” Halfman replied calmly.

She took him to her house and commanded her husband, “Build up the fire! I’m going to roast Halfman!”

The ogre heaped wood until flames roared up the chimney. “It’s ready,” he announced. “Let’s put him on!”

“Why the hurry?” Halfman asked reasonably. “I’m so thin now, I’ll barely make one mouthful. Better fatten me up first, you’ll enjoy the meal much more.”

“Sensible advice,” the ogre agreed. “What fattens you quickest?”

“Butter, meat, and red wine.”

They locked Halfman in a room and fed him lavishly for three months. Finally, he declared, “Now I’m quite fat. Take me out and kill me.”

“But first,” Halfman suggested, “you and your wife should invite your friends to the feast. Your daughter can stay and watch me while I split firewood for my own cooking.”

The ogre and his wife departed, leaving Halfman with an axe and their daughter. After chopping briefly, he called to her, “Come help me, or I won’t finish before your mother returns.”

As she held a piece of wood, Halfman raised his axe but instead of splitting the log, he struck off her head and fled like the wind.

When the ogres returned and found their daughter dead, they wept bitterly. “This is Halfman’s work!” they cried, and the ogre gave chase.

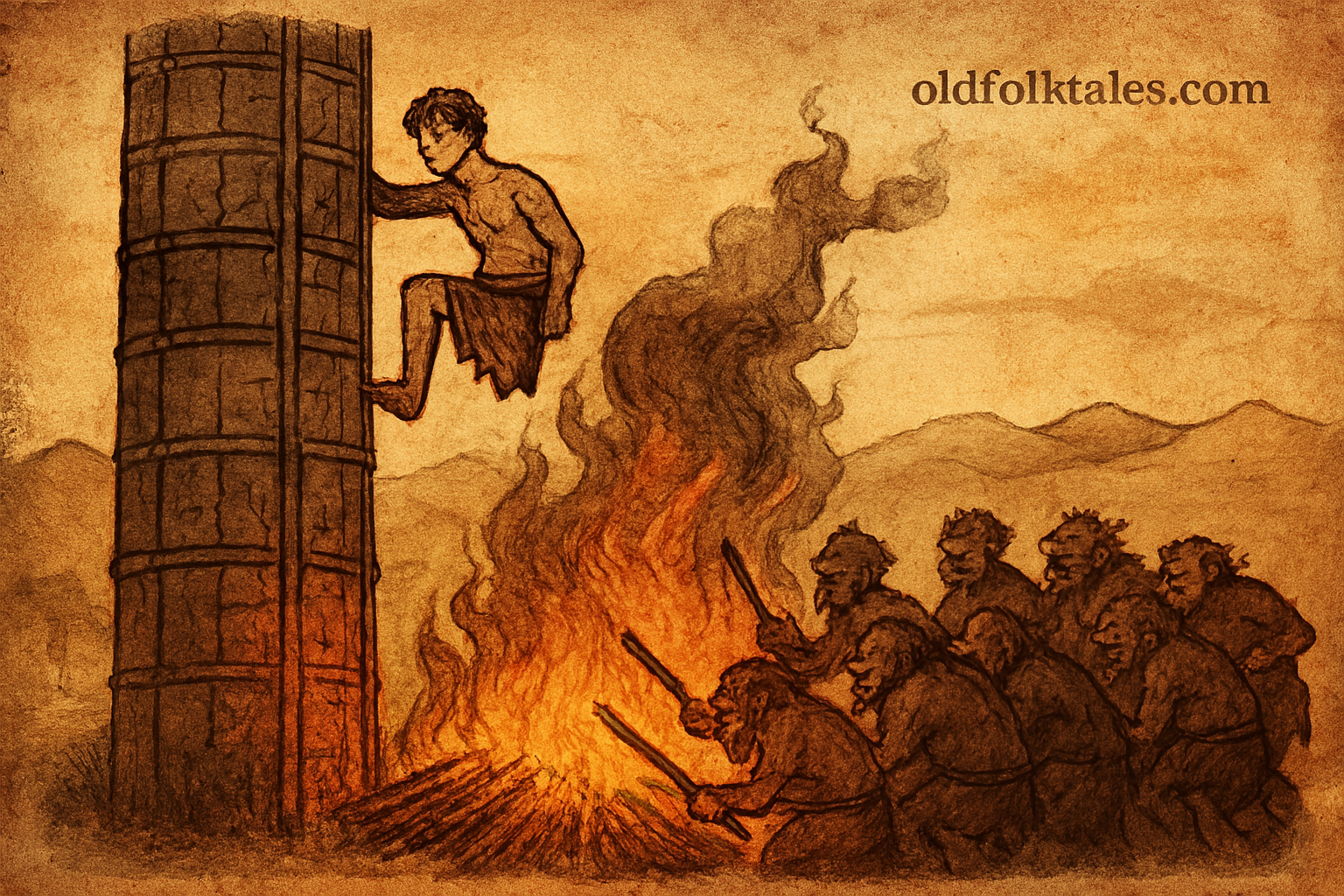

Halfman saw an iron tower and climbed to its top. Soon the ogre appeared below, searching frantically.

“Come up!” Halfman called. “You’ll find me here!”

“But how can I climb?” the ogre bellowed. “There’s no door!”

“A fish carried me,” Halfman replied. “But you must gather your relatives and bring sticks. Light a fire beneath the tower until it glows red-hot, then you can easily knock it down.”

The ogre assembled his entire clan, who built an enormous fire around the tower’s base. The iron grew hot as molten coral, but when they threw themselves against it to topple it, they caught fire and burned to death. Overhead, Halfman sat laughing.

Only the ogress survived. “You’ve killed my daughters, my husband, and all my kinsmen!” she shrieked. “How can I reach you?”

“Easy enough,” Halfman called down. “I’ll lower a rope. Tie it around yourself, and I’ll pull you up.”

The ogress fastened the rope, and Halfman began hauling her upward. But near the top, he released it. She plummeted down and broke her neck.

Halfman descended and continued his journey until exhaustion overcame him in a desert place. As he slept, another ogress woke him. “Halfman, tomorrow your brother marries your wife.”

“How can I stop it? Will you help me?”

“Yes, but on one condition: if a son is born to you, you must give him to me.”

“Anything,” Halfman agreed desperately, “as long as you deliver me from my brother and restore my wife.”

The ogress carried him on her back, reaching the town in minutes. She transformed into a scorpion, hid in a curtain, and when the brother prepared for bed, she stung him behind the ear. He fell dead instantly.

Halfman returned to his father’s house and found everyone mourning. When his father saw him, he wept, “Your brother was better than you!”

“Call my brothers,” Halfman demanded. “I have a story to tell.”

When all were assembled, Halfman recounted everything, the ogress’s deception, the switched cloths, the rescue, the jealous brothers, the attempted drowning. “Now you are a judge!” he concluded. “Who did well and who did evil—I or my brothers?”

“Is this true?” the father asked his sons.

“It is true,” they admitted shamefully.

The judge embraced Halfman. “Take your bride. May you live long and happily together!”

A year later, Halfman’s wife bore a son. Not long after, she found her husband weeping and demanded to know why.

“The baby isn’t really ours,” he confessed. “He belongs to the ogress who helped me.”

“Are you mad?” she cried.

Halfman explained his bargain. When the ogress came for the child, the boy went willingly, delighted by his new clothes and the promise of adventure.

A year passed before Halfman rode out to find his son. At midnight, the ogress appeared. “You want to ask whether I’ll take your second son as I took the first.”

“Yes,” Halfman admitted, “but please, let me see my boy.”

The ogress struck her staff into the earth, and the ground opened. The boy emerged, calling, “Dear father, have you come too?”

But when Halfman embraced him, the child struggled free. “I have a new mother and father who are better than you,” he said matter-of-factly.

Heartbroken, Halfman set his son down. “Go in peace, but tell your ogre father and ogress mother they shall have no more children of mine.”

“You won’t take any more of my parents’ children?” the boy asked the ogress.

“Now that I have you, I want no others,” she replied.

The boy turned to his father. “Go in peace. Tell my mother not to worry she can keep all her children.”

Halfman rode home and recounted everything to his wife, including the message from Mohammed, Mohammed, son of Halfman, son of the judge.

Moral Lesson

This tale teaches us that true worth comes not from physical appearance but from intelligence, courage, and moral character. Despite being born with only half a body, Halfman proves himself the wisest and most capable of all his brothers. The story also warns against jealousy and betrayal within families, showing how those who are rescued can become the worst betrayers. Finally, it illustrates the binding nature of promises, Halfman must honor his word to the ogress, even at great personal cost. The tale reminds us that debts must be paid, oaths must be kept, and sometimes the price of survival requires sacrifices that break our hearts.

Knowledge Check

Q1: What does Halfman’s physical form symbolize in this African folktale?

A: Halfman’s incomplete body represents the theme that physical appearance does not determine a person’s true worth or capability. Despite having only half a body, he possesses superior intelligence, courage, and moral character compared to his eleven “complete” brothers. His form symbolizes how society often judges by appearances while overlooking inner qualities. Throughout the story, Halfman repeatedly proves that wisdom and quick thinking matter more than physical wholeness.

Q2: Why do Halfman’s brothers try to kill him after he saves their lives?

A: The brothers’ betrayal stems from jealousy and wounded pride. Though Halfman saved them from the ogress, they cannot accept that someone they view as inferior (because of his physical form) received the most beautiful bride. Their jealousy overcomes their gratitude, revealing the destructive nature of envy within families. This betrayal is particularly bitter because Halfman specifically saved them from death, yet they attempt to murder him at the first opportunity.

Q3: What is the significance of the fish giving Halfman one of its scales?

A: The fish’s scale represents gratitude, magical protection, and the importance of helping others. The fish aids Halfman because he is innocent and has been betrayed despite his good deeds. The scale serves as a talisman—a connection to supernatural help in times of need. This motif appears in many African and world folktales, where animals offer magical objects to worthy protagonists, symbolizing that kindness and virtue attract divine or magical assistance.

Q4: How does Halfman use his cleverness to defeat the ogres repeatedly?

A: Halfman consistently uses psychological manipulation and understanding of his enemies’ greed and pride. He tricks the first ogress by switching cloths and caps, exploiting her assumption that appearances reveal identity. He convinces the second ogre to fatten him up, delaying his death. He manipulates the ogre into destroying himself by heating the iron tower. His intelligence transforms his physical weakness into strategic advantage he survives through wit when strength would fail.

Q5: What does the promise to the ogress teach about bargains and oaths in African folklore?

A: The binding nature of Halfman’s promise reflects deep cultural values about honor, oaths, and supernatural bargains in African tradition. Even though the ogress is an enemy and the cost is his beloved son, Halfman must fulfill his word. This emphasizes that promises especially those made to supernatural beings carry absolute weight and cannot be broken without severe consequences. The tale teaches that we must carefully consider the terms before making desperate bargains, as debts will always be collected.

Q6: Why does Mohammed (Halfman’s son) prefer his ogress mother to his biological parents?

A: Mohammed’s preference for the ogress demonstrates the power of environment and upbringing over blood ties. Having been raised by the ogress from early childhood, he knows no other mother and feels no connection to his biological parents. This reflects the folk wisdom that children belong to those who raise them, not merely those who birth them. It also serves as a bittersweet resolution though Halfman loses his son, the boy is genuinely happy and well-cared-for, suggesting that sometimes love means letting go.

Cultural Origin: African folktale from Andrew Lang’s Fairy Books collection, likely originating from North African