The dry season was drawing to its close, painting the African landscape in shades of golden dust and withered grass. It was that crucial time when village women moved with purpose across the parched earth, gathering dried grass for burning, clearing their farm plots with practiced efficiency, and preparing the soil for the life-giving rains that would soon arrive. The air shimmered with heat and anticipation as the community prepared for another cycle of planting and growth.

In this season of preparation lived a woman named Ngonda, whose heart was set on cultivating pumpkins in the coming growing season. She had carefully saved her seeds through the long dry months, envisioning the robust vines and golden fruits that would grace her farm. Yet she faced a significant obstacle she lacked the essential nkra, those precious wooden or earthenware rings that served as protective guardians for young plants, shielding tender seedlings from the relentless attacks of insects during their most vulnerable early growth.

With hope filling her heart, Ngonda approached her friend and neighbor, Bishi, seeking assistance in her agricultural endeavors. The bonds of friendship and community that held their village together made such requests natural and expected. Bishi, understanding her friend’s need, generously offered one of her own nkra rings, passing it into Ngonda’s grateful hands with the casual generosity that marked their relationship.

Also read: The Shape-Shifting Mother

Ngonda received the gift with joy that radiated from her very being. She hurried to her farm plot, carefully planted her precious pumpkin seed, and positioned the protective ring around it with the reverence of a mother protecting her child. The seed, nurtured by both the nkra‘s protection and Ngonda’s devoted care, responded magnificently to this combination of practical wisdom and loving attention.

What emerged from that protected soil was nothing short of miraculous. The pumpkin plant grew with such vigor and health that it became the talk of the entire village. Its leaves expanded to rival even the massive cocoyam leaves, creating a symphony of sound as they rustled and flapped against each other with every gentle breeze. The plant’s beauty was matched only by its productivity gorgeous yellow flowers bloomed in abundance, their sweet fragrance perfuming the air, while enormous buds promised pumpkins of extraordinary size and quality.

But this remarkable success planted seeds of a different kind in Bishi’s heart. As word of Ngonda’s spectacular pumpkin plant spread throughout the community, as neighbors gathered to marvel at its size and beauty, as people spoke in hushed, admiring tones about the incredible harvest it would surely yield, Bishi’s initial generosity transformed into something darker and more consuming.

Envy crept through her spirit like poison through water. Each compliment directed toward Ngonda’s plant felt like a personal slight. Each expression of amazement at the pumpkin’s growth seemed to diminish her own worth in the community. The green-eyed monster of jealousy consumed her thoughts until she could bear it no longer.

One bright morning, when the sun painted the village in warm golden light and the world should have felt full of promise, Bishi made a decision that would forever alter the course of both women’s lives. She walked purposefully to Ngonda’s compound and knocked upon her door with the firm, determined rhythm of someone who had made up her mind.

When Ngonda opened the door, her face showed immediate concern at her friend’s unexpected early morning visit. In their culture, such unannounced visits often carried news of death or disaster.

“Has someone died?” Ngonda asked, her voice tight with worry.

“No,” Bishi replied curtly.

“What then? Is your daughter sick?” Ngonda pressed, trying to understand what crisis had brought her friend to her doorstep at such an hour.

“No. I just want my nkra back.”

The words fell between them like stones into still water, creating ripples of shock and disbelief. Ngonda stared at her friend, struggling to comprehend this unexpected demand.

“Mumia gheh! Sister-of-Mine!” she exclaimed. “I can’t give you the nkra. Please be patient. Once the pumpkins have matured, I’ll pick them and give you your nkra.”

But Bishi’s heart had hardened beyond reason. She turned her lips skyward in a gesture of stubborn determination and declared, “I want my nkra the way it was when I gave it to you.”

Ngonda’s desperation grew as she realized the terrible position her friend was placing her in. The pumpkin plant had grown far beyond the protective ring its stem was now too thick and established to remove the nkra without destroying the entire plant and its precious, nearly mature fruits.

“But you are not planting any pumpkin seeds yourself,” Ngonda pleaded, her voice breaking with emotion. “Please give me one month, my sister… just one month.”

“Don’t waste your time begging. That won’t help,” Bishi responded with cold finality.

In a final desperate attempt to save her plant, Ngonda offered to share the coming harvest. “We will share the vegetables, if that’s what you want.”

But Bishi’s cruelty knew no bounds. “Give me back my nkra! I don’t want your stupid pumpkins,” she screamed, plugging her ears with her thumbs to shut out any further pleas.

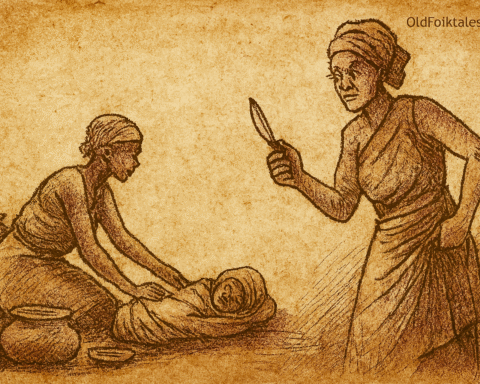

Faced with her friend’s implacable determination, Ngonda was forced into an act that broke her heart. With tears streaming down her face and hands that villagers later said must have weighed more than a ngwalii stone, she walked to her farm carrying her cutlass. The bright blade caught the sunlight as she raised it, and with one terrible stroke, she severed the magnificent plant from its roots.

The robust pumpkin plant that had been the pride of the village withered quickly under the merciless sun, its beautiful leaves curling and browning as its life drained away. Bishi collected her nkra with satisfaction, her heart singing with vindictive pleasure as she walked home, leaving behind the devastation of her friend’s dreams and labor.

Time flowed like a river through the seasons. Days melted into months, rainy seasons gave way to dry periods, and years crawled by as the cycle of agricultural life continued. Women planted and harvested, rested and worked again, while children grew and new ones were born to carry on the eternal rhythm of village life.

Eventually, the ancestors smiled upon Bishi, blessing her with the gift she had long desired after three daughters, she finally gave birth to a son. The joy of this moment was beyond measure in a culture where sons carried special significance, serving as future caretakers of their parents and carriers of family legacy. Bishi threw a magnificent feast in celebration of this precious child, inviting the entire community to share in her happiness.

Yet even in her joy, one concern clouded Bishi’s contentment. She possessed none of the traditional protective strings that Beba customs required for newborn children not the beautiful beaded nkre jigida, not the findi ntsa, not even the modern red bangles known as ndegh waba. These weren’t mere decorations; they were essential protective amulets that strengthened a child’s neck bones and posture while guarding against illness and evil spirits.

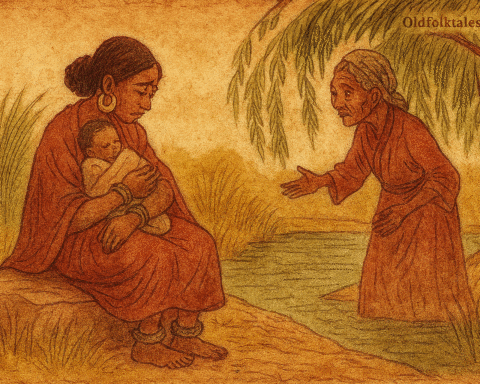

For days, Bishi worried about this gap in her son’s protection. Then, like sunrise breaking through darkness, the solution came to her. How could she have forgotten? Ngonda was renowned throughout the village as the finest nkre weaver, a master craftswoman who created these protective strings during the rest periods between farming seasons. Her work was celebrated for its perfect thinness, soft texture, and remarkable strength.

Without hesitation, Bishi hurried to Ngonda’s house and knocked upon the door, requesting help in creating a protective string for her newborn son.

Ngonda, ever practical, suggested a simpler alternative. “Why don’t you buy one of those modern red bangles, not the white ones, mind you. You know the white ones bring bad luck. Those things are easy to maintain and adjust as the child grows older.”

But Bishi insisted on traditional craftsmanship. “I’d rather you weave one for my son using the ndia tou threads from our forest.”

Ngonda, perhaps remembering their friendship despite past pain, offered Bishi a beautiful nkre she had already created. Bishi accepted it gratefully and placed it around her son’s neck with ceremony and pride, secure in the knowledge that her child was now properly protected according to ancestral traditions.

The protective string worked its magic beautifully. Bishi’s son grew into a plump, lively boy whose health and vitality became the envy of other mothers. His cheeks were said to shine like python eggs the highest compliment that could be paid to a child’s robust appearance. Daily, Bishi offered libations to the ancestors, thanking them for this precious son who would care for her in her old age after her daughters married and joined other families.

One morning, as Bishi busied herself preparing the day’s meal before heading to her farm, she heard a soft but determined knock at her door. Stepping carefully over the burning logs in her fireplace, she pushed open the door and peered through the smoke at a shadowy figure standing in her doorway.

“Who is it?” she asked, wiping the smoke’s sting from her eyes.

As her vision cleared and the smoke dissipated, her heart nearly stopped beating. There stood Ngonda, but this was not the friend she remembered. This woman’s eyes burned with an intensity that seemed to bore holes through Bishi’s very soul. The village wisdom rang true: when you see a snake lying silent by the wayside, you know it has swallowed its prey.

Bishi attempted a smile, but her face felt frozen with dawning dread.

“I have come for my nkre jigida,” Ngonda announced with quiet, terrible determination.

Bishi tried to deflect, greeting her friend as if nothing had been said, asking about the early morning visit, mentioning her plans for farm work. But Ngonda would not be deterred.

“You heard what I said. I’ve come for my nkre jigida.”

The terrible parallel crashed over Bishi like a waterfall. The same impossible demand she had made years ago was now being turned back upon her, but with stakes immeasurably higher.

“Eh! You want your string back? But how can I give it to you without harming my son?” Bishi cried, finally understanding the full horror of what was being asked.

Ngonda’s response echoed with the wisdom of proverbs: “A snuff-box has no right to sneeze. Only you have the answer to your question.”

Bishi wept and pleaded, her heart breaking as she begged for mercy for her innocent child. She offered to cut the string and have it rewoven, to buy a replacement, to provide any compensation Ngonda might desire. But Ngonda remained unmoved, her heart as hardened as Bishi’s had been years before.

“What? No, you can’t do that. I want it whole, the way it was when I gave it to you,” came the merciless response.

When Bishi continued to plead, reminding Ngonda that this was a child, a human being, her only son, Ngonda’s laughter rang out cold and terrible.

“Do you remember my pumpkin?” she asked, her voice cutting through Bishi’s sobs like a blade. “It’s true that if you keep scratching the anus you’ll touch excrement. Hurry up! The sun is already up and the weeds are eating up my groundnuts.”

Faced with the same impossible choice she had forced upon her friend, Bishi understood that the circle of cruelty was complete. In the end, she made the same terrible decision that her friend had been forced to make, and gave Ngonda the nkre jigida in the only way possible.

Moral Lesson

This haunting folktale serves as a powerful warning about the consequences of cruelty and the cyclical nature of evil actions. Bishi’s initial act of spite in demanding her nkra back, destroying her friend’s thriving pumpkin plant, ultimately returned to destroy what was most precious to her. The story teaches that cruelty begets cruelty, and that those who show no mercy should expect none in return. It emphasizes the African wisdom that our actions have consequences that may return to us in ways we never expect, often when we are most vulnerable.

Knowledge Check

Q1: What were nkra and why were they important in this African folktale? A1: Nkra were wooden or earthenware rings placed around young plants to protect them from insects during early growth. They represent the tools necessary for agricultural success and community survival.

Q2: What is the significance of the nkre jigida in African culture according to this story? A2: The nkre jigida were traditional protective strings worn around newborns’ necks to strengthen neck bones, maintain posture, and protect children from illness and evil spirits essential for a child’s wellbeing.

Q3: What does the pumpkin plant symbolize in this folktale? A3: The pumpkin plant symbolizes the fruits of hard work, community cooperation, and the prosperity that comes from sharing resources. Its destruction represents the waste that results from envy and spite.

Q4: How does this story illustrate the concept of poetic justice? A4: The story shows poetic justice through Bishi experiencing the same impossible choice she forced on Ngonda both women lose what is most precious to them due to inflexible demands that mirror each other perfectly.

Q5: What role do traditional proverbs play in this West African tale? A5: Proverbs serve as moral commentary and wisdom, such as “A snuff-box has no right to sneeze” and warnings about sleeping with fowls, providing cultural context for the characters’ actions and consequences.

Q6: What does this folktale teach about friendship and community relationships? A6: The story warns that breaking the bonds of friendship through envy and cruelty destroys the mutual support systems that hold communities together, leading to tragic consequences for all involved.

Source: The sacred door and other stories, Cameroon folktales of the Beba (1st ed.). Ohio University Press.