Long ago, when the world was still young and the forests stretched wide across Corisco Island, all animals lived freely beneath the sky. Goat was among them, wild and untamed, his horns sharp and his beard swaying proudly as he wandered the hills. At that time, goats roamed in herds, feeding on fresh leaves and grasses, climbing rocks and leaping about with joy. Yet Goat had a restless spirit, and he was never satisfied.

Goat often quarreled with the other animals. When Antelope grazed peacefully, Goat pushed her aside. When Monkey leapt through the branches, Goat complained that the fruits fell on his back. Even Leopard grew weary of Goat’s stubborn bleating, for he was always making demands and refusing to follow the ways of the wild. Goat wanted more comfort, more food, and more attention than the forest could give.

One season, the rains failed. The streams grew thin, and the grass dried into brittle stalks. Many animals searched deep into the forest for water and green shoots. Goat, however, complained bitterly. “Why must I wander so far for food? Why must I suffer thirst when there must be an easier life somewhere?” He grew weaker, for he refused to endure hardship as the others did.

READ THIS: The Goat’s Grand Tournament

It was then that Goat noticed the villages of the humans nearby. From a distance, he saw their gardens full of cassava and yams. He smelled the smoke of their fires and saw bowls of water placed near their huts. The humans seemed to live with abundance even in the dry season. Goat licked his lips and thought to himself, “Perhaps I will find comfort among them. Perhaps their homes will give me the life I desire.”

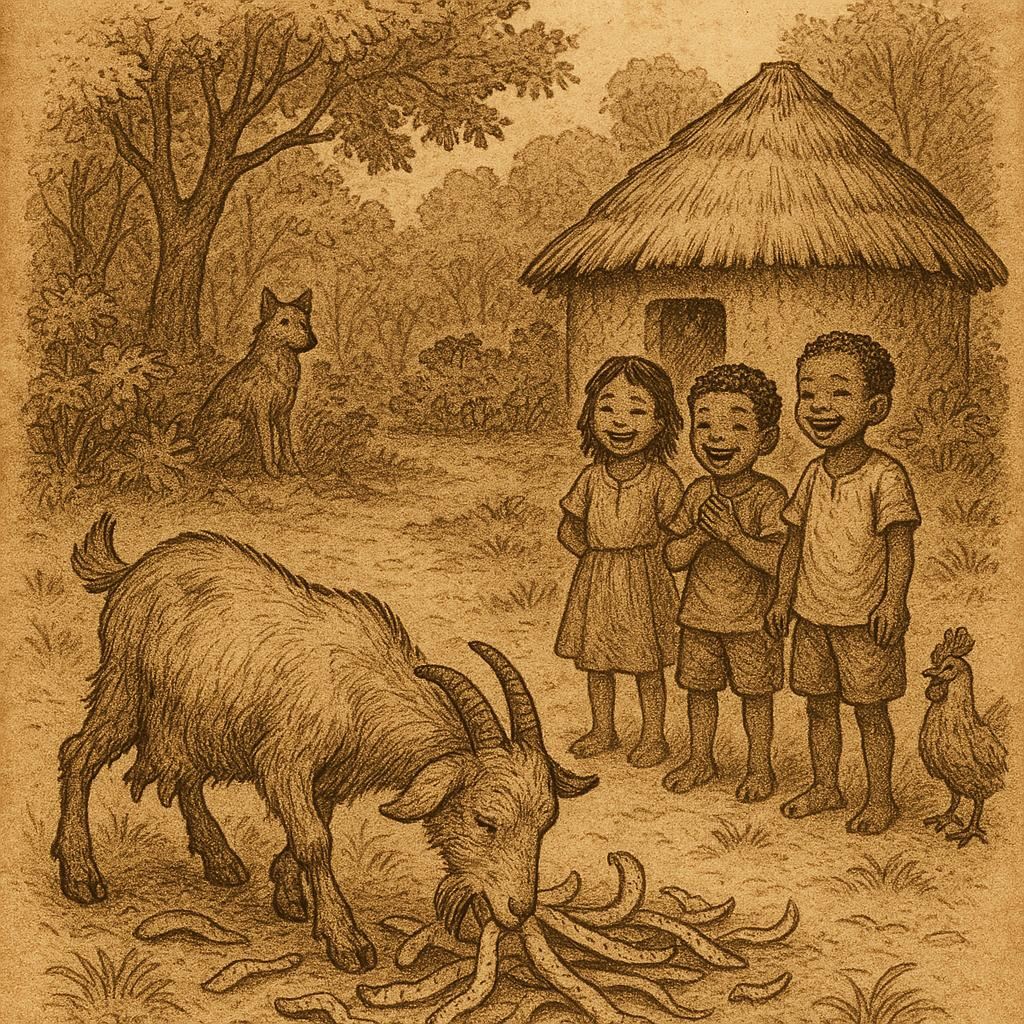

One evening, Goat crept closer to the village. The children noticed him and clapped their hands in delight. They threw him handfuls of peeled cassava, which Goat devoured greedily. The women fetched water and set it near the gate, and Goat drank until his thirst was gone. That night, he lay near the hearth of the villagers, warm and satisfied, while the forest animals shivered in the cold darkness.

When dawn broke, Goat returned to the forest to boast. “You foolish creatures,” he said to Antelope, Monkey, and the rest. “While you starve, I have eaten cassava. While you thirst, I drink clear water. While you freeze, I sleep by the fires of men. I have found a better life!”

But the others mocked him. Leopard growled, “Humans are dangerous. They hunt us for food and skins. Do not be deceived by their kindness.” Monkey chattered, “You will not be free. Their homes will bind you. Better to be wild than trapped!” Yet Goat paid no heed.

Day after day, he returned to the village, eating scraps from the cooking pots and drinking water from the jars. The humans began to notice how tame he was, how easily he followed them. Soon they tied a rope around his neck and led him into a pen. Goat was not troubled; he had food, shelter, and company. He grew fat on garden plants and cooked leftovers.

When the forest animals passed near the village, they saw Goat chewing contentedly. “Look at you!” cried Antelope. “You no longer leap through the hills. You no longer climb the rocks. You are tied and fed like a servant!” But Goat only bleated happily and answered, “What does freedom matter when my belly is full and my body warm?”

As seasons passed, goats multiplied in the villages. They lived close to humans, eating from their gardens and sleeping by their fires. Some were even sacrificed in rituals or shared at feasts, but Goat accepted this fate, for he preferred comfort over freedom. Meanwhile, the wild animals remained in the forests, lean and free, always searching for food and water.

Thus it was that goats became domestic, choosing the lives of humans over the struggles of the wild. To this day, Goat still bleats in every village, wandering among huts, eating cassava peels and yam leaves. His spirit of complaint and restlessness led him to trade freedom for comfort, and so he became one of the household animals of mankind.

Moral Lesson

The story of Why Goats Became Domestic teaches that seeking comfort without considering its cost can lead to the loss of freedom. Goat chose the warmth and food of humans over the struggles of the wild, and though his belly was filled, his independence was gone. The tale reminds us that true contentment often lies in balance, not in surrendering freedom for ease.

Knowledge check

Why was Goat unhappy living in the wild with the other animals?

Goat disliked the hardships of the forest and longed for comfort, food, and warmth.What did Goat first notice about the human village?

He saw gardens full of food, bowls of water, and fires that promised warmth and abundance.How did the humans treat Goat when he first approached the village?

They fed him cassava peels, gave him water, and allowed him to sleep near their fires.Why did the other animals warn Goat against living with humans?

They believed humans were dangerous hunters and that Goat would lose his freedom.What eventually happened to Goat after staying in the village?

He was tied up, fed by humans, and became one of their household animals.What is the main moral of Why Goats Became Domestic?

That comfort gained too easily can cost one’s freedom, and balance is wiser than surrendering independence.

Source: Benga folktale, Corisco Island, Equatorial Guinea (recorded by Robert H. Nassau, 1914).